Project summary

- Client: Synergy on behalf of the Bath Abbey Parochial Church Council

- Location: Bath, Somerset

- Sector: Heritage conservation

- Project duration: March 2018 – July 2022

- Key fact: This project has won numerous awards, including three at the prestigious RIBA Awards 2024. It was also nominated for Rescue Project of the Year 2020 by Current Archaeology magazine.

Wessex Archaeology was commissioned by Synergy to provide a range of services at Bath Abbey, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This striking landmark was the subject of an ambitious, multi-million-pound initiative, entitled the Bath Abbey Footprint Project, to restore parts of the building and create additional facilities. Specifically, the project had three principal aims, all of which required the expertise of our multi-disciplinary team:

1) To repair the collapsing floor, which had a huge number of post-medieval burials beneath it

2) To replace the Victorian heating system with an eco-friendly, underfloor alternative powered by geothermal heat from the neighbouring Roman baths

3) To create additional on-site facilities, such as a refectory and interactive heritage centre, that would benefit worshippers, visitors and future generations alike

Owing to the age and design of the building, the Bath Abbey Footprint Project, funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, was an incredibly complex undertaking that required an agile team, flexible thinking and clever solutions.

Unearth historic news from Bath Abbey

Site history

The history of the site dates back to 675 AD when King Osric gave land to Abbess Bertana to build a convent, which later became a monastery. In 1090, the Bishop of Bath, John of Tours, ordered construction of a new Norman cathedral priory, which was finally completed in approximately 1150. It was later demolished and replaced by the current abbey church in around 1480-1525. The church was closed by King Henry VIII and it wasn’t until 1573, with the support of Queen Elizabeth I, that the local community started repair work, which was completed in 1617. The church underwent another major renovation in the 1860’s.

Archaeological investigations within historic structures

To repair the floor and install the new heating system, stonemasons lifted the ledger stones and the construction team hand-excavated a metre of disturbed soil whilst being monitored by our archaeologists. When archaeological features were uncovered, they were cleaned and recorded by our team. Where possible, archaeological remains were preserved in situ but where this was not possible, the remains were carefully hand excavated by our archaeologists.

Further works were undertaken in the extensive network of underground cellars to the south of the abbey. Following the removal of modern flooring, our team of archaeologists carefully excavated a complex sequence of prehistoric, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, medieval and post-medieval remains.

In total, we recorded human remains from over 100 burials, including Anglo-Saxon, medieval and post-medieval, as well as the disarticulated remains of more than 2,200 individuals. Some of these remains were covered by a Church of England Faculty Licence, so had to stay on-site. To enable analysis, we set up a laboratory within one of the abbey’s nearby buildings where the human remains were processed and assessed by our in-house osteoarchaeologists. They have since been taken to the chapel at Abbey Cemetery and will remain there for the foreseeable future.

Conducting our work within a church that had been altered considerably over its history, the project team had to respond to the complications this presented in terms of structural issues. One example relates to the huge church organ loft held up by wooden pillars. As the team dug down, they realised that one of the pillars, which was holding up about 40 tonnes, was ‘floating.’ A major structural and health and safety concern, we worked with the abbey team to install purpose-made supports whilst ensuring the original heating design plan could remain the same.

In other parts of the site, historic cellar walls were discovered to be poorly founded and in need of underpinning. This required excavations beneath the walls through complex Roman archaeology. Undertaking these excavations whilst safely achieving what was needed by the construction team required close co-operation between our archaeologists and the engineering and groundworker teams.

Deploying experienced staff members from across our organisation was key to the success of this project. Not only did our health and safety team offer crucial advice throughout, but also the project had one consistent archaeological lead who had a deep understanding of the architecture and was able to liaise with key stakeholders as and when problems arose. In addition, our team of archaeologists were experienced in complex excavations involving human remains.

Above: UAV's enabled the team to capture Bath Abbey from a unique perspective, providing detailed photogrammetric records.

Recording historic features for conservation and interpretation

A multi-disciplinary effort, this project also relied on the expertise of our geomatics specialists. These experts implemented a bespoke GPS recording method to support the complex excavation and assisted our archaeologists in creating 3D photogrammetric models of the archaeological features. A total of 213 models were produced and these were then ‘stitched’ together to create a 4D reconstruction of the entire excavation.

We also produced a comprehensive 3D model of the newly restored floor, as well as models for the eastern and western stained-glass windows. These three models utilised the latest photogrammetric technologies to record detail down to the millimetre, with some of the images presented on panels that are on display at The Discovery Centre, the abbey’s interactive heritage visitor space. Indeed, whilst we captured data for our own recording purposes, we have been able to extend its value by sharing it with the public.

Another example is our drone survey of the west side of the abbey. This survey is now available in The Discovery Centre as an interactive display and allows visitors to zoom in and gain a much closer look at the various design details.

Specialist input and analysis

Owing to the long history of the site, we uncovered a large number of finds and features that dated as far back as the Mesolithic period (approx. 10,000 BC) and required specialist input from a range of in-house teams. Whilst working in the underground vaults, we discovered flint blades, bladelets and cores, suggesting that Mesolithic people gathered near the hot springs and created their own tools. Due to the significance of this discovery and the potential for environmental evidence, our geoarchaeologists helped devise a detailed sampling strategy that determined the nature of the deposit sequence that the flint was found in, along with our in-house flint specialists.

The osteoarchaeologist and field team excavating in the vaults discovered rare Anglo-Saxon ‘charcoal’ graves, thought to date from the 10th and 11th centuries. This unusual burial rite involved lining the base of a grave with charcoal, with more charcoal sometimes placed above the body. The meaning of this practice is unknown, but it is thought to have been a respectful ritual associated with high-status burials.

Grave site statistics

- Anglo-Saxon: 61 graves; disarticulated remains of 251 individuals

- Medieval: 25 graves; disarticulated remains of 256 individuals

- Post-medieval: 26 graves; 21 lead coffins; disarticulated remains of 1,759 individuals

- Total burials: 112 graves; disarticulated remains of a further 2,266 individuals

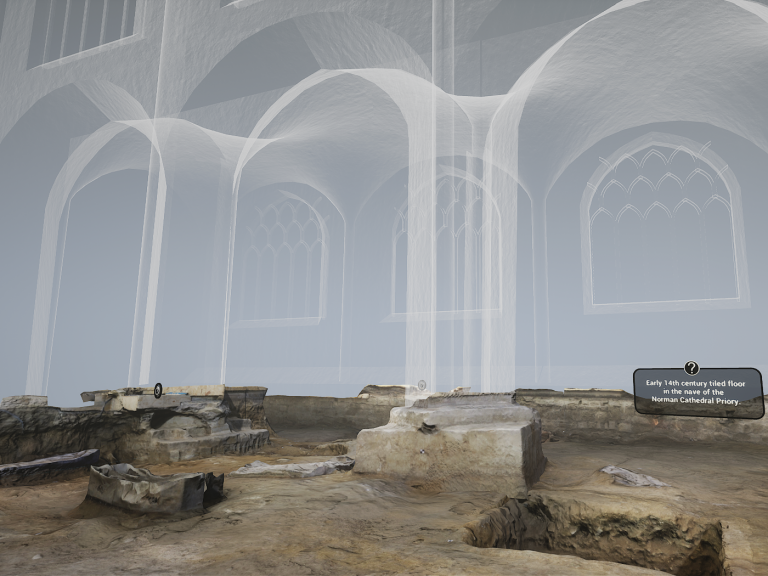

Excavations within the abbey nave revealed a beautiful early 14th-century tiled floor, which offered a unique glimpse into what the former Norman cathedral would have looked like. The brightly coloured tiles, which were likely laid on the orders of Bishop Droxford in the late 1320s, were found approximately two metres below the current floor level. Following detailed recording of the floor, including a 3D model, the team preserved the remains in situ, covering the floor with a protective membrane and a layer of inert sand.

Below is a list of further finds and how our experts handled them:

Lead coffins – Coffins that were intact were encased in purpose-built wooden boxes and lifted by construction workers for re-burial in the Abbey Cemetery crypt. Ruptured lead coffins were hand excavated.

Fragments of Jacobean plasterwork – We discovered hundreds of fragments, all of which were quantified on site. Some were re-buried, some were retained for deposition at Bath Abbey Archive and additional samples were retained for use as handling material for Bath Abbey.

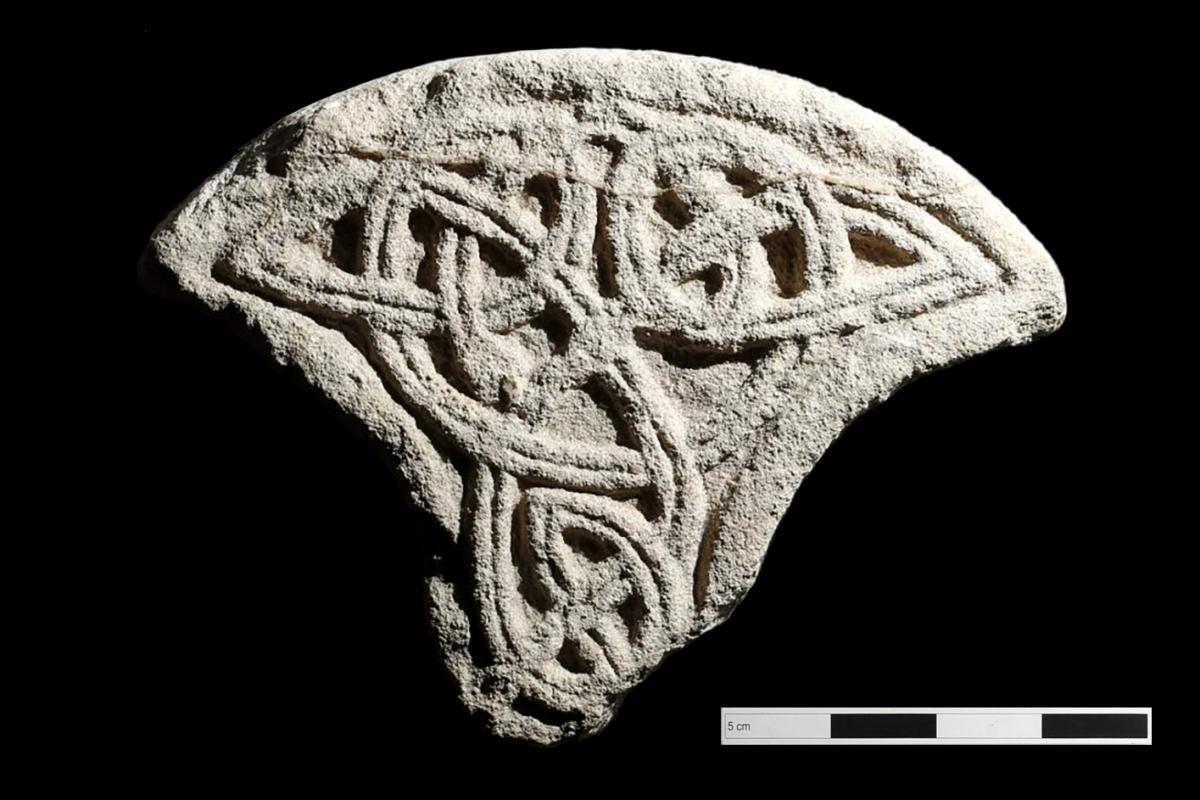

Large pieces of medieval stonework – All stonework was recorded on site and either re-buried or retained for further study.

Post-medieval coffin furniture – This was recorded on site and re-buried.

Pre-historic flint, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, medieval, post-medieval and modern pottery, glass, metal and animal bones – These finds were collected and bagged by context before being washed, conserved, marked and analysed at our head office. All finds will be deposited at Bath Abbey Archives.

We have since completed the post excavation assessment and are currently in the process of writing a monograph.

Left, middle: Fragments of two Late Saxon stone crosses from Bath, both discovered in the 19th century. In the collection of the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution. Right: Late Saxon carved stone reused as medieval grave cover excavated in 1993. Held by Bath Abbey Archive.

Interpretation and public engagement

Throughout our involvement in this remarkable project, we worked closely with partners on community engagement and stakeholder communications, creating an array of content to keep the local community informed and to promote the project. Along with numerous blog posts that appeared on the Wessex Archaeology website, we produced a series of short films for YouTube and featured in various publications including Bath Newseum, Current Archaeology and the Danish broadsheet Politiken. Notably, the project also appeared on the BBC’s primetime archaeology series Digging for Britain, which features significant archaeological excavations around the UK.

Another important focus was maintaining regular engagement with nearby residents. As well as regular open days, we held training sessions to enable volunteers to record memorials and our engagement experts delivered education sessions using the Virtual Reality model of the excavations. In addition, our project archaeologists have spoken about the excavation work to many specialist interest groups, including Friends of Bath Abbey and the Somerset Archaeology & Natural History Society.

“This was a once in a lifetime project,” reveals our project manager Bruce Eaton. “The complex nature of excavating in a historic abbey meant we had to flex our approach continually but what we gained in archaeological knowledge was incredible. For me, being able to share the wealth of new information with the public made this project stand out.”

Videos from our excavations