As our journey, highlighting results from archaeological excavations in Salisbury, has progressed, the emphasis has shifted from the medieval city, the buildings the residents occupied and the refuse they discarded to explore the roots of human occupation in the area. This has taken us beyond the boundary of the original city to discover Saxon cemeteries and settlements and, last week, traces of Iron Age communities, who farmed the land before the Romans arrived. Many of these discoveries have shown that even the smallest excavations can provide unexpected discoveries. Some fulfil the objective of extending the story of Salisbury much further back in time.

In 2007 Wessex Archaeology excavated two small trenches at 120 Fisherton Street before the site was redeveloped.

Trench 1 (left) and Trench 2 (right) of the 120 Fisherton Street excavations

The location, squeezed in between the railway embankment and buildings fronting onto Fisherton Street, lies at the edge of the River Avon floodplain. This area formed part of the early medieval settlement of Fisherton Anger and lay on the main route out of the city leading to Wilton.

The site in Fisherton Street in 2007 (left) and in 2020 (right)

No traces of the medieval community were found; however, a significant discovery was made, which was represented by a small group of worked flints. The edges of each piece remained very sharp, indicating that the objects had probably not been moved far from where they had been made, used and discarded. Furthermore, the inclusion of numerous blades, long narrow pieces of flint, placed the most likely time at which they were made to the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age). This period marks a crucially important time in the occupation of Britain, spanning the gap between the final retreat of the ice cap, approximately 10,000 years ago and the introduction of agriculture and more settled communities about 4,000 BC. It is a time when Britain became separated from the continent and the landscape became increasingly more wooded as the climate warmed.

Modern reconstructions of Mesolithic flints, showing microliths used as drill bits (left) and arrow heads (centre), and blades used as knives (right). These examples show how small flints can be attached to wooden handles using natural resins

Despite being such an important part of the national story, traces of the Mesolithic can be very difficult to identify, there can be very little to find! These people are most well known for their worked flints, most notably microliths (micro – small, liths – stones) which were used as drill bits and to tip arrow shafts. Blades, which characteristically have long, straight edges, made ideal knives. The Mesolithic groups also made the first hafted wood-working axes, which made it possible to chop down trees to frame weather-proof structures.

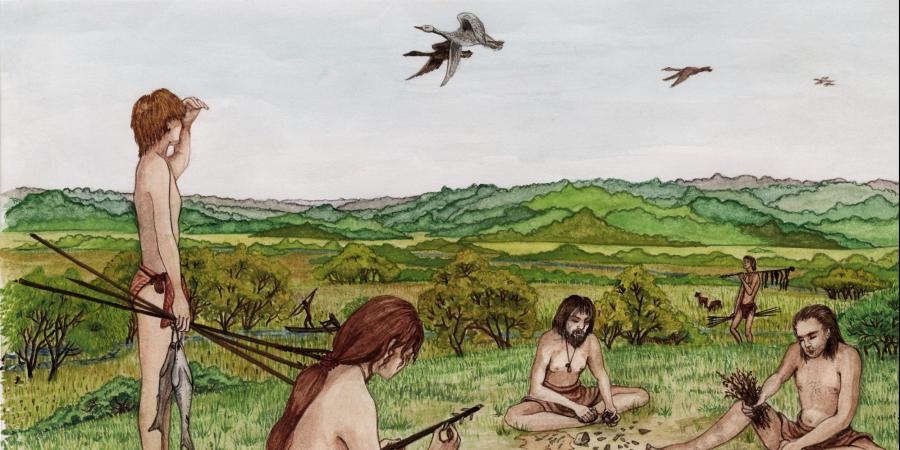

The Mesolithic communities predominantly occupied the river valleys; as such the findings in Fisherton Street were entirely in keeping with what we might expect. They lived by hunting, fishing and feeding from the edible plants that grew along the riverbanks. They were essentially mobile, no doubt moving within the network of five rivers for which Salisbury is well known. They probably moved within a defined, familiar territory, knowing where natural resources occurred, exploiting these as they became seasonally available and probably revisiting certain locations on a systematic basis. It is very likely that they knew how to control their environment, possibly using fire to burn-off undergrowth to encourage regeneration of plants for grazing animals. We know from work elsewhere in Britain that they could build functional skin-clad or wooden shelters or huts, structures which leave few or no visible traces in the ground. Evidence of their camps is invariably restricted to scatters of discarded worked flints and burnt debris from hearths, features which provided foci for heat and social life. They developed a spiritual understanding and buried and cremated their dead.

An artist's interpretation of Mesolithic life

These groups of people remained custodians of Britain for approximately 5,000 years. Traces of their presence have been found elsewhere in the Avon valley, at Downton and Amesbury; however significant discoveries are, as we’ve seen in Fisherton Street, often totally opportunistic. Other sites undoubtedly remain hidden, yet each discovery adds important evidence of human use of the Avon valley, in this case also supplementing the story of Salisbury itself.