The Bath Abbey Footprint Project is ambitious in scope. As well as repairing the historic Abbey floor and replacing the Victorian heating system with an innovative low-carbon heat-exchange system which utilises the outflow of geothermal spring water from the Roman baths, the project is also creating new facilities within the Georgian vaults below street level and refurbishing Kingston Buildings south of the Abbey.

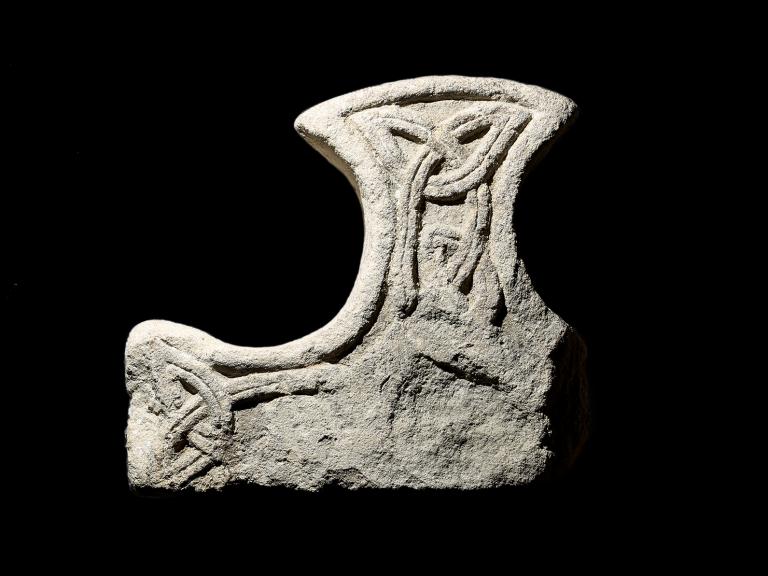

Both the vaults and Kingston Buildings lie within an area which was once occupied by the south cloister of the huge Norman cathedral , which preceded the present Abbey church. There has been remarkable preservation of archaeological features and deposits below the Georgian ‘formation’ levels. During Wessex Archaeology’s excavations robbed out cloister walls, medieval burials, a late-Saxon cemetery and early medieval ‘dark earth’ deposits have all been encountered. And, as you would expect from a site located at the heart of the Roman settlement of Aquae Sulis and immediately to the east of the Roman Baths and Temple of Sulis Minerva, these deposits sealed some impressive Romano-British archaeology.

One discovery made during the excavation of a pipe trench within the basement of Kingston Buildings shows just how well preserved some of the remains are. Project archaeologist Chris Hambleton describes what was revealed below a layer of Roman demolition material:

“As we teased away a corner section of this layer, to our amazement below lay in-situ tessellated Roman tiles. The tiles were made of creamy coloured sandstone cubes that averaged 2-3cm in size. The whole floor area exposed was more than a metre long and half a metre wide.”

This was an internal floor of a large building whose walls were also recorded in the vaults to the north and the alleyway to the south of Kingston Buildings. The building appears to respect the alignment of the town walls, thought to have been constructed in the late-2nd or early-3rd century AD.

To the west of this building, there were one, or possibly two, Roman roads that converged with a wide open area immediately to the east of the Roman baths and temple complex. This open area was defined by stone-lined gutters to the east, and a ditch and wall to the west; both of which followed the alignment of the Roman baths. Senior Project Officer Cai Mason has the job of interpreting these remains:

“We aren’t yet certain of this wall’s function: it may form part of a building, or it could be a boundary that defined the eastern extent of the baths complex. Whatever its original function, the wall appears to have remain standing for several centuries, and later served as a boundary that demarcated the extent of a late Saxon cemetery containing charcoal burials. North-south aligned cart ruts across the hard-packed gravel surface to the east of this wall show that this was a heavily-used thoroughfare, which probably formed an important route through the Roman settlement.”

As well as the structural remains, a large assemblage of Roman finds, including coins, painted wall plaster, glassware, bronze and bone tools and pottery, has also been recovered from the excavations. Further assessment and analysis of the finds will be undertaken by Wessex Archaeology’s specialists, helping to build a detailed picture of life in this small corner in the heart of Roman Bath.

Bruce Eaton, Project Manager