The ss Mendi: a ship history forgot

History records many ships as lost at sea, far from home. The exact circumstances of the sinking are often poorly known, the deaths of passengers and crew recorded a silent tragedies.

Few of those ships are famous in one continent and all but forgotten in another. The steam ship SS Mendi is one of them.

In the dark and fog of the night of Wednesday 21st February 1917, the ss Mendi was rammed by another ship. It was an accident, but with a deep gash in its side, the Mendi was doomed. She sank 25 minutes later and almost 650 men died.

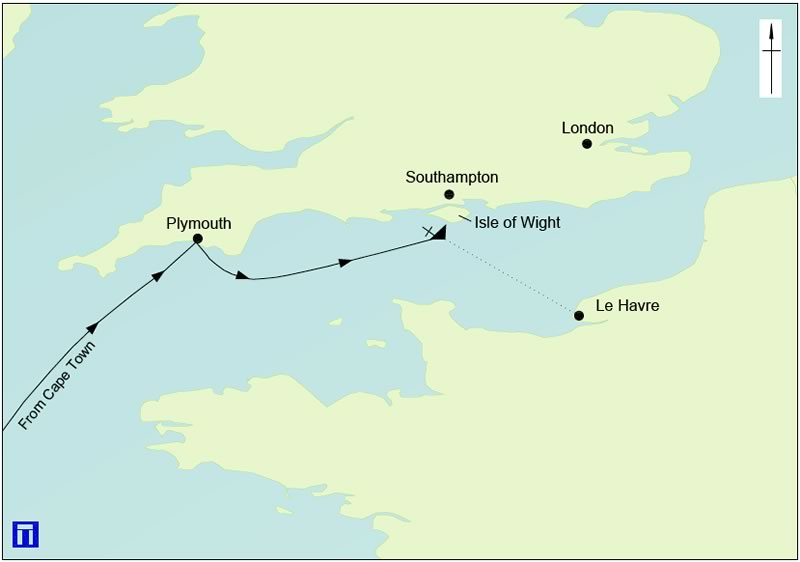

The wreck lies off The Isle of Wight, in the English Channel. In Britain the story of the SS Mendi is almost unknown. In South Africa she is famous; a symbol of a racist past and an icon of unity and reconciliation.

Global conflict

The First World War rapidly became a new type of war. It was the first war to be seen as global in extent. The scale of death and injury on the Western Front was unprecedented.

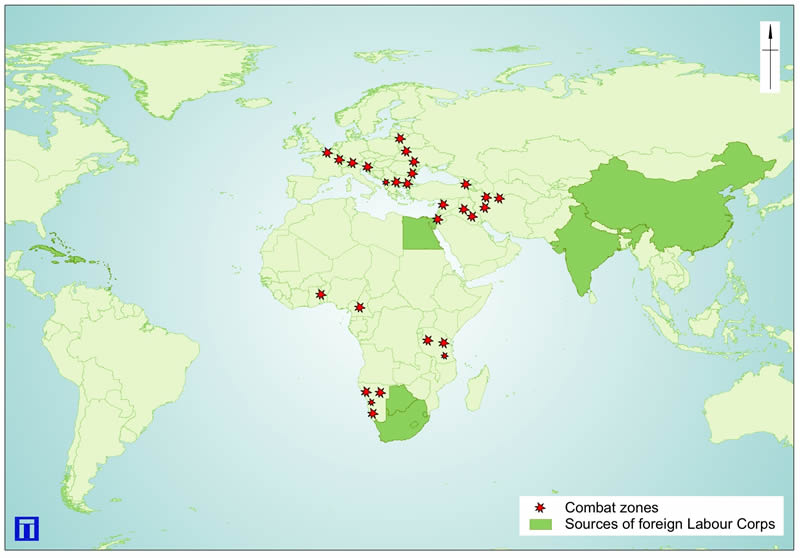

As more and more soldiers were sent to the trenches, keeping them supplied became even harder. Soon Conscientious Objectors and the medically unfit had been drafted in to serve as labourers. As the scale of conflict continued to escalate, troops were brought in from around the British Empire. And from across the Empire and beyond came labourers: the Foreign Labour Corps.

A white man's war

For the administrators of the Empire the demands of the war posed a dilemma. The need for more men was clear, but mindful of the possible consequences, there was a reluctance to train and to arm non-whites, and especially Black Africans.

But the need for more men, especially labourers continued to grow and the pressure increased. Some of this pressure came from black and coloured subjects of the empire who wanted to serve. Eventually a compromise was reached; they could serve in supporting roles, under the command of white Commissioned Officers. The non-combatant Foreign Labour Corps were born. Soon units were formed around the Empire, from India to the West Indies, totalling 300,000 men.

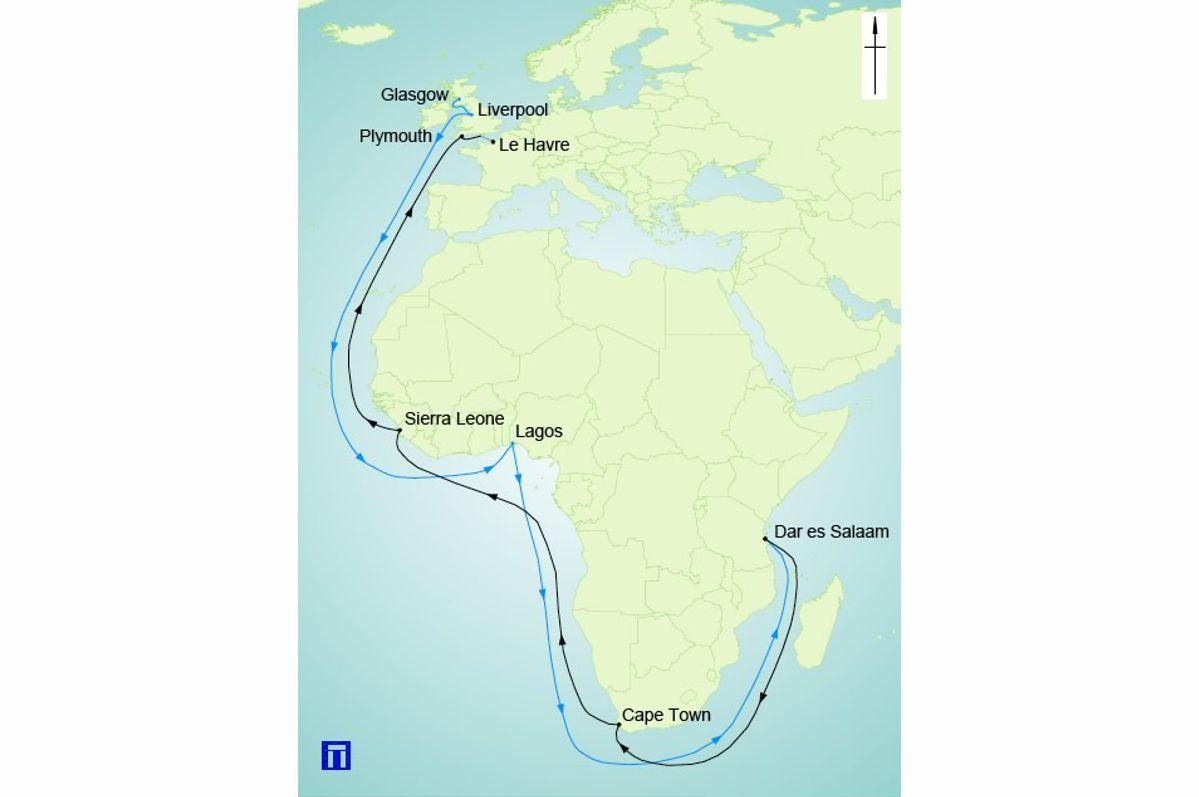

Over 70,000 of them formed the South African Native Labour Corps, working first in German South West Africa and East Africa, and then in France. It was for the French port of Le Havre that the Mendi was bound in February 1917. Aboard were 823 men of the 5th Battalion South African Native Labour Corps.

The sinking of the Mendi

The Mendi had left Cape Town on January 25th, 1917. She stopped three times, delivering cargo and taking on supplies. Firstly in Lagos in Nigeria and then in Sierra Leone, where a small gun was fitted to the stern. Her last stop was Plymouth, England, on February 19th. She sailed for France the next day. On this last, hazardous, leg of her journey she was escorted by the destroyer HMS Brisk.

The sea was calm but after midnight thick fog surrounded the Mendi. She had to slow down until she was barely creeping forward. As German U-boat submarines hunted in the area, slowing down was dangerous. By 04:57 a.m. the Mendi was 11 nautical miles (20 km) off the southern tip of the Isle of Wight.

Suddenly the steamer Darro emerged from the dark and fog. The Darro was a mail ship, twice the size of the Mendi. She was sailing at full speed. She drove into the side of the Mendi amidships, cutting into hold where men lay asleep.

The aftermath

The damage was fatal. As the Mendi listed further and further to starboard, none of the life boats on that side could be launched. Although the port life boats were launched and there were life rafts and lifebelts, few of the men could swim. Most had never seen the sea before they boarded the Mendi at Cape Town.

The Mendi sank within 25 minutes. Almost 650 men, both crew and Labour Corps died; drowned, or killed by the cold.

Inexplicably the Darro offered no help. The survivors, picked up by HMS Brisk and then other ships, told tales of bravery and selflessness. The story of the chaplain, the Reverend Isaac Dyobha leading a Death Dance has become famous in South Africa. According to the story, the men formed ranks on deck and Reverend Dyobha addressed them;

‘Be quite and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do. You are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers. Zulus, Swazis, Pondos, Basothos and all others, let us die like warriors. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries my brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais back in the kraals, our voices are left with our bodies.’

The South African parliament stood to mark the loss of the Mendi, the second worst loss of South Africans in World War One. An Inquiry was held and the Master of Darro was found to blame, but controversy raged as to why so few survived. The survivors, over 200 of them, were taken back to England before being assigned to other battalions and sailing for France to work in the docks and in construction.

They were the last men of the South African Native Labour Corps to be sent to Europe. The Armistice that ended the First World War came into effect at 11:00 a.m. on the 11th November, 1918.

After the War, none of the black servicemen on the Mendi, neither the survivors nor the dead, or any other members of the South African Native Labour Corps, received a British War Medal or a ribbon. Their white officers did. This was South African decision. Black members of the South African Labour Corps from the neighbouring British Protectorates of Basutoland (modern Lesotho), Bechuanaland (Botswana) and Swaziland did receive medals.

The legacies

The story of the Mendi received little mention in histories of the War written in its aftermath but the memory of the men and the injustice dealt to them after their death was not forgotten. Told by word of mouth rather than the written word, the story became an icon of unity and a symbol of injustice in the struggle against apartheid.

Since the ending of apartheid, the loss of the Mendi has become part of official histories and marked in many ways, including remembrance ceremonies and the making of memorials. The Mendi Memorial in Heroes Acre at the Avalon Cemetery in Soweto was unveiled by President Nelson Mandela and her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in 1995. Meanwhile the Mendi itself lay far away, all but lost to history.

In Britain the names of all those who died that night are inscribed, along with those of other service personnel who have no grave but the sea, on the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton. But it was not until 1974 that the wreck of the Mendi was identified correctly.

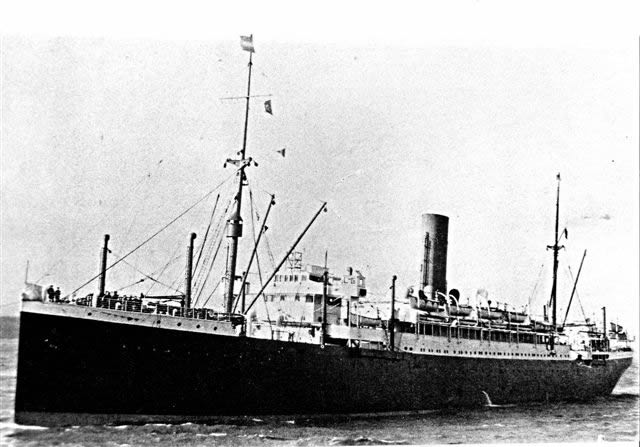

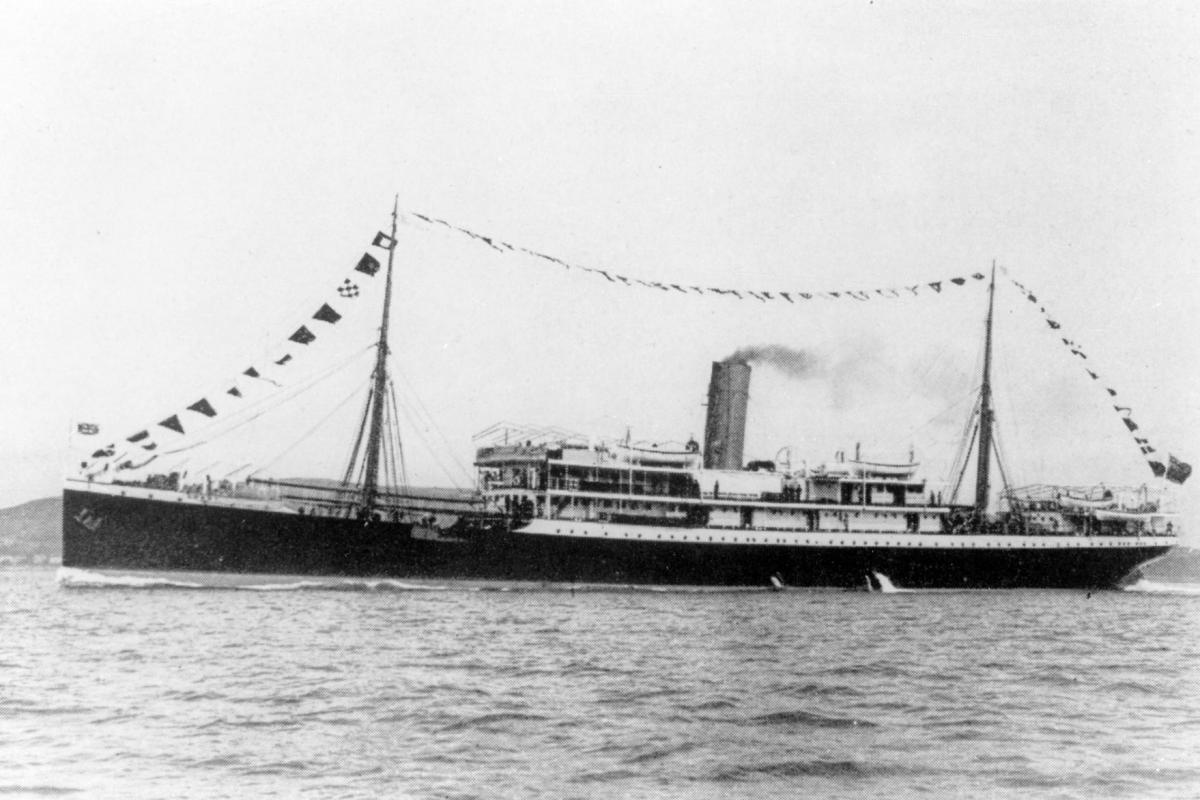

The Ship

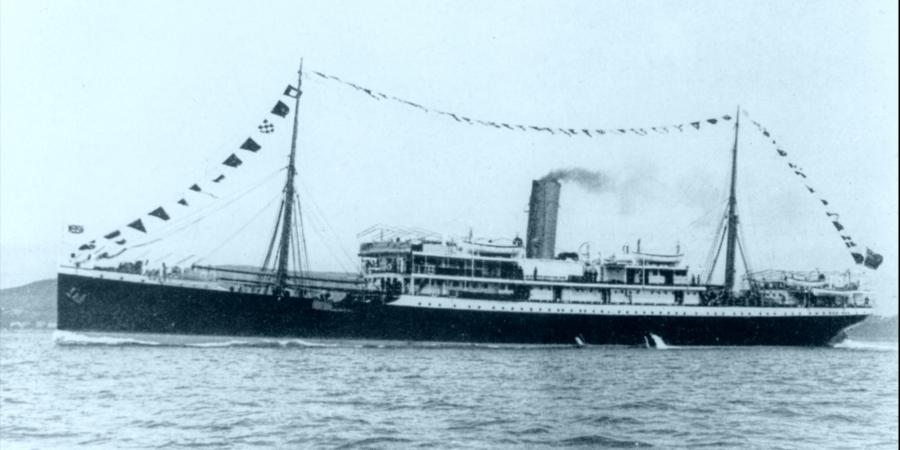

The Mendi was launched on the River Clyde in Glasgow in 1905. The 4230 ton steamship was built by Alexander Stephen and Sons. She was owned by the British and African Steam Navigation Company, part of the Elder Dempster Group, and used on the Liverpool to West Africa mail and cargo run, a route that followed part of the earlier slave trade, from Britain to Africa and then America.

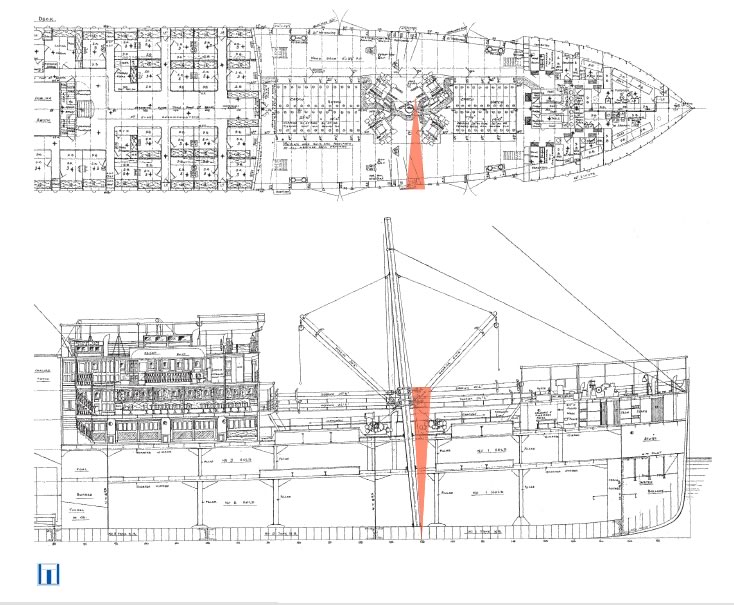

In the autumn of 1916 the Mendi was contracted to the British Government for war service. She was sent to Lagos, Nigeria to be fitted out as a troop ship. Three cargo holds were converted for troop accommodation. The officers were housed in the existing passenger accommodation above deck.

The Mendi transported Nigerian troops to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to fight in German East Africa before returning to South Africa to set out on her fateful voyage to France.

A few photographs of the Mendi survive and there are technical drawings showing her construction in the National Maritime Museum. Even as a troop ship she retained her steamship livery. Her hull and funnel were painted black, the bridge and cabins were buff, and the waterline was red. Apart from the gun that was added to the stern in Sierra Leone while she was on her way to France, the changes to the Mendi were mostly internal.

The Wreck

The wreck was first located in 1945 but she was not correctly identified as the Mendi until 1974. She lies in deep, murky, water and so has rarely been visited by divers. Those who have, say that she sits upright on the sea bed. Parts of the bow and stern are quite well preserved but she has broken apart in the middle and parts of the boilers and engine can be seen.

Some small things can also be seen, such as some of the plates that the men would have eaten off. It was the crest of the British and African Steam Navigation Company on some of these plates that allowed divers to identify the wreck as the Mendi.

There is a growing awareness that the Mendi can be treated as war grave but some pieces, such as porthole surrounds have been brought to the surface by divers as souvenirs or to sell. Some have been given to museums in Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, and on the Isle of Wight.

The future

In today’s South Africa the story of the Mendi has a prominent role in reconciliation and is used a symbol of reconciliation. In Britain this significance is largely unknown, and her story is obscure. Around the world the roles of the various Foreign Labour Corps in the First World War has been little explored.

Archaeology provides a way to rediscover a part of the story of the Mendi that has been lost. It is hoped that scientific surveys of the wreck can be made later in 2007. Hi-tech geophysical surveys and Remotely Operated Vehicles with cameras can allow us to see beneath the sea and at last discover a ship that history forgot.

A preliminary study of the Mendi was commissioned by English Heritage in 2006.

To download the Teacher's Pack for this site follow this link.

Links

-

Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum, Arreton, Isle of Wight

-

University of Glasgow Archive Services (a resource for shipbuilding on the Clyde)

-

Merseyside Maritime Museum - Maritime Archives and Library

-

h2g2 (BBC site)

To find out more information read the report below.