As described in

Along Prehistoric Lines: Neolithic, Iron Age and Romano-British Activity in the Former MOD Headquarters, Durrington, Wiltshire

By Steve Thompson and Andrew B. Powell

Published by Wessex Archaeology, 2018

Available to purchase at Oxbow Books

Introduction to the excavation

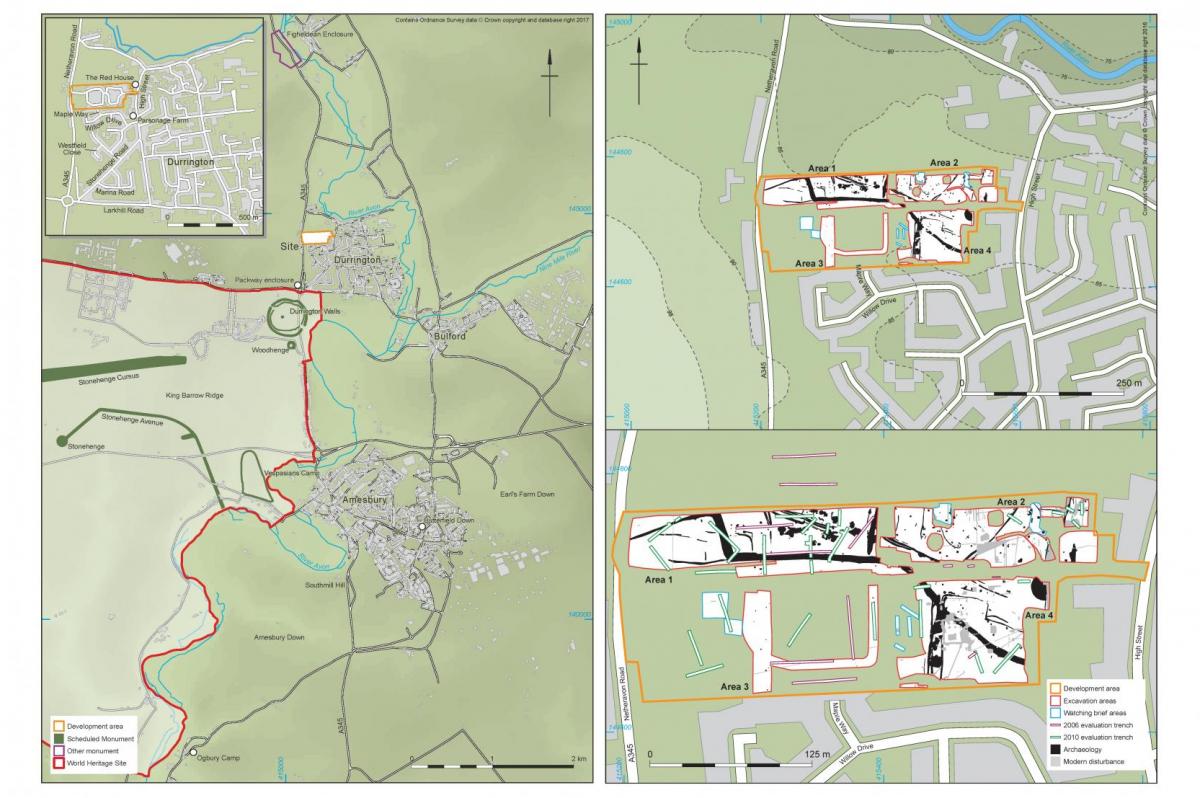

On the site of the former MOD Headquarters in Durrington, a programme of archaeological excavation and watching brief (2000−2012) was undertaken by Wessex Archaeology ahead of the site being redeveloped into residential housing by Persimmon Homes South Coast. This revealed archaeological evidence spanning thousands of years and as far back as the last Ice Age. The excavation links the area around the village of Durrington into the larger ritual landscape of prehistory and the subsequent periods of habitation of the later Iron Age and Roman periods. Uncovering various large linear prehistoric features, it appears the excavated areas also show episodes of occupation of a ritual and mundane nature.

The earliest find is a section of an Allerød palaeosol (a preserved buried land surface) visible in the side of a prehistoric ditch. This dates from the end of the Younger Dryas Period, c. 9500 BC, a period of colder and drier climate with large glaciers in Northern Europe. While no artefacts or material such as charcoal from fires that might indicate human activity were found, it raises the possibility that Upper Palaeolithic material could be preserved elsewhere in the landscape.

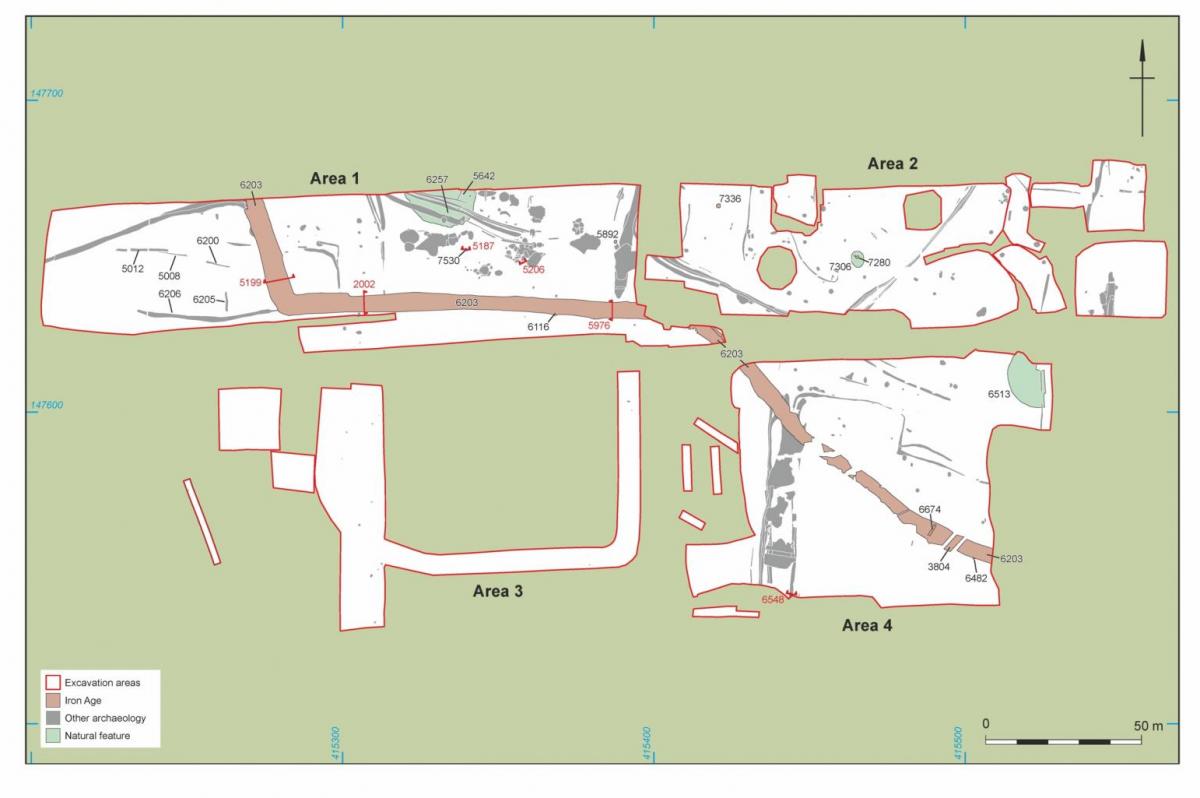

The earliest archaeological evidence dates to the Late Neolithic, c. 2600 BC, with structural evidence as well as landscape use similar to that found elsewhere in the Stonehenge ritual landscape. The Neolithic evidence consists of a setting for an alignment of large oak posts, alongside several pits with deliberate deposits, flint knapping, as well as the use of natural features for burial. The proximity to the ritual complex of Durrington Walls places this site into the complex Stonehenge ritual landscape

Durrington Walls is one of the bigger henges (a bank and ditch earthwork, often with multiple entrances) in Britain, containing a large Neolithic settlement and closely related to the site of Woodhenge. With the site of Durrington Walls linked with feasting and consumption, it is possible the site at MOD Durrington, whilst outside the current World Heritage boundary, could be intrinsically linked with the ritual and ceremonial activity happening throughout the landscape at this time.

The only Bronze Age evidence found was an urned cremation burial (1800 BC), with little Iron Age evidence apart from a few cremation burials. The Bronze Age burial was preserved in situ in an area of parkland within the new development.

In the Late Iron Age, over 2000 years ago, a large defensive earthwork was constructed just before the Roman Conquest of 43 AD.

The Romano-British activity resulted in the possible levelling of the earthwork and the spreading of settlement from the interior north of the ditch. The excavation uncovered pits, pottery kilns, ovens and small fields arranged in a ‘ladder’ pattern. A small quantity of Romano-British building materialfound during the excavation hint at the existence of a possible building in the vicinity, however, no buildings were identifiedin the excavated areas.

Initial occupation and Late Neolithic activity

The Late Neolithic evidence found during the excavation consists of several key elements: two alignments of postholes across the series of trenches, alongside many pits containing typical Neolithic finds, as well as a series of natural solution hollows. The evidence for Neolithic activity close to the site of Durrington Walls and the Stonehenge ritual landscape suggest that it continued some distance beyond what was previously known and today mostly marked within the current World Heritage Site boundary. It is suggested that this activity could best be seen as Andrew Powell as stated as ‘further components of a fine-grained web of interconnectivity’. It could also be likely that the activity around the solution hollows and postholes could be contemporary.

The initial construction of the oak posts was radiocarbon dated to 2670-2550 cal BC slightly earlier than the settlement at Durrington Walls (2490-2455 cal BC). Radiocarbon dates on animal bone, found in the postholes, indicate that the removal or decommissioning of the post alignments happened during 2575-2470 cal BC. At a time just before the arrival of the Beaker people.

There was no deposition of artefacts during the postholes construction, only after the posts were removed or had decayed. Some of the animal bone comes from pig and cattle, both animals having importance in the ceremonial Durrington complex, where they were consumed in feasts.

Flintwork found across the site at MOD Durrington includesseveral fine arrowheads for hunting as well as tools representing the more mundane elements of Neolithic life, including scrapers and chisels.

Several finds have been uncovered alongside many artefacts such as ceramic and worked flint typical of the period. The most impressive, at least in size where the pieces of worked sarsen stone blocks found in the posthole alignment, the largest weighing in at 15 kg, with two smaller fragments, interpreted as broken flakes, being found alongside it.

The use of sarsen as a material to construct stone circles such as Stonehenge and Avebury may suggest this material had some importance to the occupants of Neolithic Durrington, however it is suggested that the stone was discarded after being unable to be worked further. It is also broadly contemporary with the sarsen phase of Stonehenge, however it is possible sarsen was more commonplace than it is today as a number of solitary standing stones are known locally.

A piece of worked ‘bluestone’ known as a biface was found in a later ditch close to the intersection of the two posthole alignments. This object is similar to ones found at Stonehenge and is almost certainly of Neolithic date. However, whilst it is likely to have been brought to the site at this time, it could equally be a Romano-British curio or trophy. ‘Bluestone’ is a key material of non-local rocks, many of which were brought from Wales, and most famous for its use at Stonehenge and the ritual activity taking place there.

The linear spread of Grooved Ware pits present at MOD Durrington again link the site with the settlement and ritual activities at Durrington Walls. It appears that the material present in the pits, such as pig bone, pottery and flintwork issimilar to many other assemblages from Late Neolithic pits in the Stonehenge landscape and elsewhere in Southern England. Such pits tend to involve the ritual burial of occasional exotic objects and materials but more often than not the refuse from feasts and occupation.

The other worldly symbolism associated with below-ground features and subterranean activity, especially near water, such as the River Avon, is not limited to the deliberately dug pits, there is also activity around the solution hollows. The three hollows are all different but two are linked by the amount of worked flint and knapping debitage found within them, which could suggest a common significance. It is no coincidence that this area of natural hollows was further embellished with settings of posts and Grooved Ware pits.

A Late Neolithic cremation burial was found in the bottom of the shallowest hollow, deposited underneath a layer of worked flint. The cremation burial is a critical find, as it supports the hypothesis that cremation was more widespread than previously thought during the Mid−Late Neolithic until the appearance of Beaker inhumations burials. The flint scatter above the burial suggests the importance of flintworking, possibly associated with burial and the otherworld, supported by the flint evidence in the larger hollow.

The larger hollow would have been a visible landscape feature, remaining geologically active throughout prehistory, it is almost impossible to estimate how deep it was during the Late Neolithic. It was a key focus of activity, primarily knapping, however there may have been others which we have no record for. There was evidence of deliberate deposition of flint gravel around the edge of the hollow, which could have been intended to alter appearance and create a surface to engage with certain activities.

The environmental sampling evidence from the excavation revealed many hazelnut shells, with scant cereal remains. This could indicate the local population predominantly exploiting the seasonal resources available in the area.

The Bronze Age, Iron Age and onwards

The excavation found very little Bronze Age evidence, the only feature being a cremation burial in an Early Bronze Age Collared Urn, which was preserved in situ. There is also a piece of cattle mandible found in the smaller hollow, radiocarbon dated to 1690−1520 cal BC alongside a sherd of pot, of the same date in the Late Iron Age enclosure ditch.

There was no evidence of Early Iron Age activity in the excavation and the Middle Iron Age is predominantly represented by burials and a small selection of pottery. Other finds included a hooked blade, three clay slingshots, an antler comb and two worked bone gouges. The Middle Iron Age burials range in age from two children aged 4−5 to two adults aged 30−45.

The Late Iron Age is dominated with the construction of a large enclosure ditch and bank, going north-west to south-east. The earthwork is near the scale of some Iron Age Hillforts, 290 m long, and taking an irregular course south-east across the excavation, it varied between 5−7.8 m wide and 3.6−4 m deep. Its odd course is similar to the Figheldean Enclosure to the north of the excavation. Figheldean, is the site of another irregular earthwork, enclosing a section of land between the ditch and River Avon.

There is little direct dating evidence for the earthwork, however, a cow mandible found in the base of the ditch gives a radiocarbon date of 20 cal BC−60 cal AD, and a pit cut by the ditch gave a date of 90 cal BC−60 cal AD. It is thought that this was constructed just before the Roman Conquest of Britain, exemplifying the heightened sense of pressure and danger shown in the construction of other large-scale Late Iron Age earthworks across the South of England. Interestingly, there is a lack of associated features, such as living spaces or storage, which would be assumed to be within the protection or boundaries of the enclosure. This could be because the associated settlement is closer to the river than the excavation boundaries.

Romano-British period

After the Roman Conquest of 43 AD, the earthwork was filled in, it could have been assumed that there was no defensive necessity, as the invasion had already happened. The solution hollows were reused as rubbish dumps, as well as Roman grain storage pits reused as refuse pits.

There were 7259 pieces of pottery dating from the Romano-British period, as well as evidence of a trackway and field ditches and boundaries. This trackway had a metalled surface and stretched across the previous earthworks, which had been levelled and filled in during the Romano-British period of occupation. Although Romano-British roof tiles and pieces of plaster were found, there were no foundations or buildings uncovered. It is suggested that there could be a substantial Romano-British settlement closer to the river, which the field systems and trackway lead to.

A ‘ladder arrangement’ of field boundaries was found across the site, with markers and field systems stretching off to the north east. The presence of this agricultural designation presents a clear move away from the ritual activity of the Neolithic.

There were a series of ovens and kilns across the excavation site, however, it is unclear whether they were for cooking and baking or for grain processing and possibly brewing. Three kilns were excavated, with much ceramic ‘waster’ material still in situ. These ovens and kilns appear to have been located in specific zones of activity, in relation to the field markers and other contemporary activity on the site.

There were two late Romano-British burials, both inhumations, both of females over 45 years old, possibly dating between the 2nd-4th century AD.

There are a wide range of artefacts found from the Romano-British period, with glass beads to metalwork being found across the site and in refuse pits. The metalwork includedbrooches of various types and iron tools.

Some of the most puzzling artefacts from the entire excavation come from this period, 18 pottery disks clipped into roughly circular shapes. Suggestions for their use include spindlewhorl production, gaming counters or even ‘pessoi’ for cleaning after defecation.

There was little post-Roman evidence from the excavation, with most stemming from ditches and possible boundary cuts, as well as a number of pits containing animal burials, including pig and horse.

Durrington’s foundation is ancient having seen many different cultures and cosmologies through its existence, and each successive period of occupation leaving distinct marks in the ground below the fields and the streets of the village we see today.

By Senior Research Manager, Alistair Barclay and Finn Cresswell