Wessex Archaeology is proud of its role in helping Historic England to protect two new nationally important historic wrecks.

The first of these, UC-70, was a First World War German mine laying submarine built in 1916 in Hamburg. Carrying their mines in tubes forward of the conning tower, German mine laying submarines operated around the UK throughout the war. The minefields they laid were a particular menace to coastal shipping and regularly closed off both British and French ports. Large numbers of British and allied merchant ships also fell victim to them, threatening the British war effort. The presence of German submarine bases in parts of Flanders that the Royal Navy was unable to attack effectively from the sea was one of the reasons why the British Army and its allies fought the notorious and unsuccessful Third Battle of Ypres, or Passchendaele as it became known. However, it was only by the adoption of the convoy system and a massive effort to bolster anti-submarine defences in the seas around Britain that the U-boat menace was ultimately defeated.

Until August 1918, very late in the war, UC-70 was a successful ‘boat’ (submarines are always boats, not ships). Operating from Flanders as far afield as the Bay of Biscay, it sank 33 Allied ships of all sizes with its mines, torpedoes and deck gun. At one point it was sunk by a British shell whilst alongside in the captured port of Ostend, but it was quickly salvaged and patched up.

On the 21st August, UC-70 left Zeebrugge for a war patrol off the English east coast. What happened next is unclear, but seven days later a patrolling British bomber followed an oil slick off Whitby. Reaching the end of the slick, the pilot, Lieutenant Arthur Waring, saw the tell-tale shadow of a damaged submarine just below the surface. Waring dropped a bomb close to it. Shortly afterwards the British destroyer Ouse arrived and dropped depth charges through a patch of oil that had come to the surface after the bomb had exploded. More oil and debris came to the surface. Believing the U-boat to have been sunk, British divers were quickly on the scene. These brave men, known as the ‘Tin Openers’, squeezed or cut their way into German submarine wrecks in the hope of finding code books or other intelligence material. They found the sunken submarine on the seabed. There appeared to have been no survivors.

Like many submarine wrecks around the UK coast, the UC-70 drew the attention of late 20th century salvors. By 1991 both bronze propellers had been taken for the valuable metal, even though the wreck is not reported to have been sold for salvage and despite the concern of locals who regarded the wreck as a war grave. Recreational divers also started to visit and the wreck became quite a popular dive site.

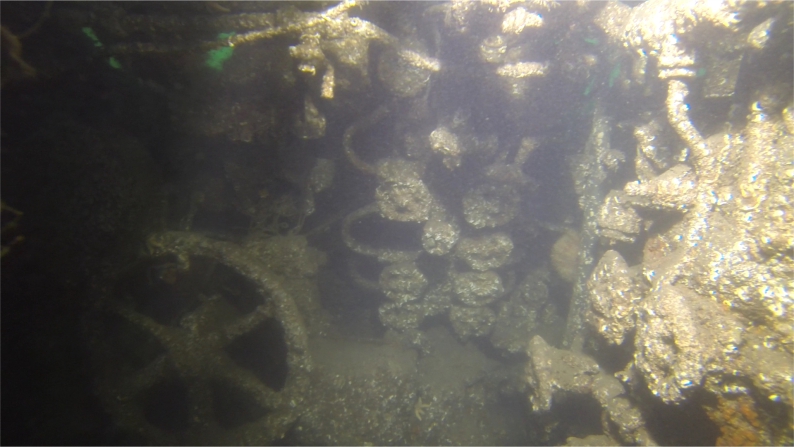

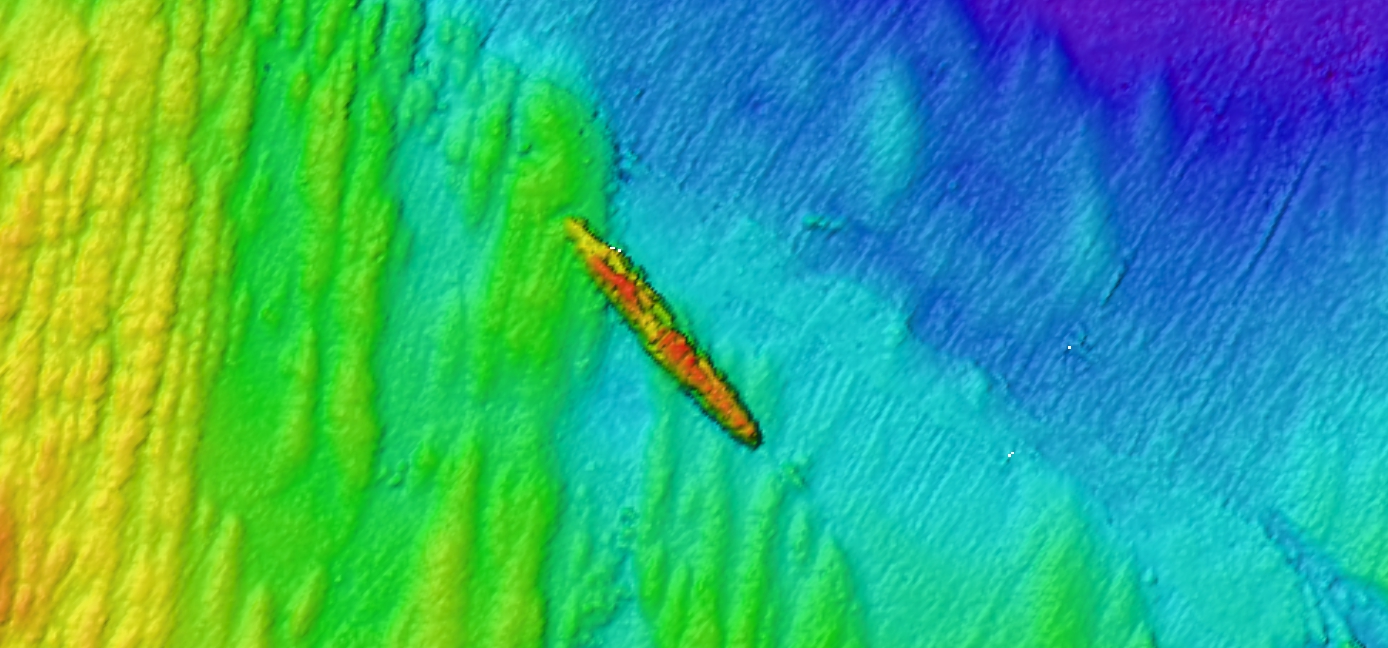

The wreck of the UC-70 was identified as being of possible historical and archaeological importance in a desk-based study of submarine wrecks around the English coast commissioned by Historic England. Then, in 2016, an opportunity arose for Historic England to send a Wessex Archaeology dive team to survey it, part of a wider programme of submarine wreck investigations carried out by us off the North-East coast. Arriving during a rare period of good visibility and using CEFAS geophysical survey data provided through the UKHO, our dive team was able to locate and inspect the submarine over the course of a couple of dives in August 2016. UC-70 was observed to be partially intact and lying upright at 25m depth. Considering how close it was to the coast, it was obviously fairly well preserved and its pressure hull resisting the corrosion that is now causing many First World War shipwrecks to rapidly collapse. However, evidence of what may have been late 20th century salvage was quickly spotted. Much of the bow was missing and a large hole in the stern section of the pressure hull (the part of the submarine that does not flood when it dives and within which the crew live) suggested the violent removal of the stern torpedo tube, probably to obtain its valuable non-ferrous metal.

In 1918 the Royal Navy divers had found evidence – open hatches – that some of the crew had managed to get out of the submarine. However, they also found the bodies of some of the crew within. The divers, whose work was both arduous and hazardous, were concerned only with identifying the submarine and finding material valuable to the British war effort against the submarine menace, so many bodies would have been left. In 2016 we saw how salvage can disturb human remains in submarines, as a human skull was seen through the hole in the stern of the submarine. Although we have a crew list, we do not know who this was. Our best guess is that as it was found in the aft torpedo room, it may have been one of the ‘torpedo men’ who operated the stern tube.

Following receipt of our report, Historic England decided to recognise the historical and archaeological significance of the UC-70 and its vulnerability by designating it under the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973. Whilst ultimately we cannot hope to protect the submarine from the depredations of time and tide, we are proud of our role in helping Historic England recognising the importance of this small part of our First World War heritage.

Working with local volunteers and experts is a key feature of our work for organisations such as Historic England and Historic Environment Scotland, and Wessex Archaeology is grateful to local divers and researchers John Adams, Mike Radley, Anthony Green and Chris Robinson for their help during and after the fieldwork, and also to the Holderness Coast Fishing Industry Group for the use of their research vessel Huntress for diving.

Watch out for a news article on the second, rather older wreck coming soon.

By Graham Scott and Paolo Croce, Wessex Archaeology Coastal & Marine