Archaeologists working in Wiltshire have identified a unique network of First World War tunnels under Salisbury Plain.

The tunnels are part of a First World War battlefield used to train men to fight in and under the trenches of France and Belgium. The soldiers have left the mine galleries deep in the Wiltshire chalk but they have also left their names – over a hundred inscriptions written by soldiers training on Salisbury Plain between 1915 and 1918.

The trenches and the tunnels beneath them have been found during archaeological work in advance of new Army housing at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain. Archaeologists have been working alongside specialist engineers and tunnel specialists to investigate the underground battlefield.

The First World War is famous for its miles of trenches. Trench systems also included dug-outs − underground chambers used as troop shelters, headquarters, medical posts and stores - that were relatively safe from the bombs and bullets on the surface but mining also had more malign purposes. Both sides dug tunnels under no-man’s-land between the opposing trench lines. Once under the enemy trenches they laid large explosive charges to blow holes in the lines of trenches. Both sides played cat and mouse, digging towards each other and trying to stop the enemy from placing their explosives.

At Larkhill there are dug-outs and underground mines snaking under no-man’s-land with the defenders’ counter-mines seeking them out. There are listening posts, where soldiers used stethoscopes to hear the enemy miners’ pick axes at work. There is also evidence of soldiers learning how to lay small charges to blow the enemy tunnel and bury the enemy soldiers alive.

Martin Brown (WYG) Archaeological Consultant to the Army Basing Project said:

‘This is the first time anyone has found and excavated tunnels used to train the sappers and miners before they were deployed overseas. We have found them as part of the largest single investigation of First World War training trenches anywhere in the world. Our excavations have revealed this story for the first time. That we didn’t expect these underground tunnels shows that much remains left to discover, even from only a century ago.’

The trenches and mines are directly related to battles fought 100 years ago: The Somme in 1916 began with a number of mines blown, as did Arras, which began on Good Friday 1917, while the Battle of Messines was heralded on 7 June 1917 by the detonation of 19 mines under the German trenches. As one officer remarked before the Messines attack, the mines would ‘change the geography’.

Leaving their mark – 100 years on

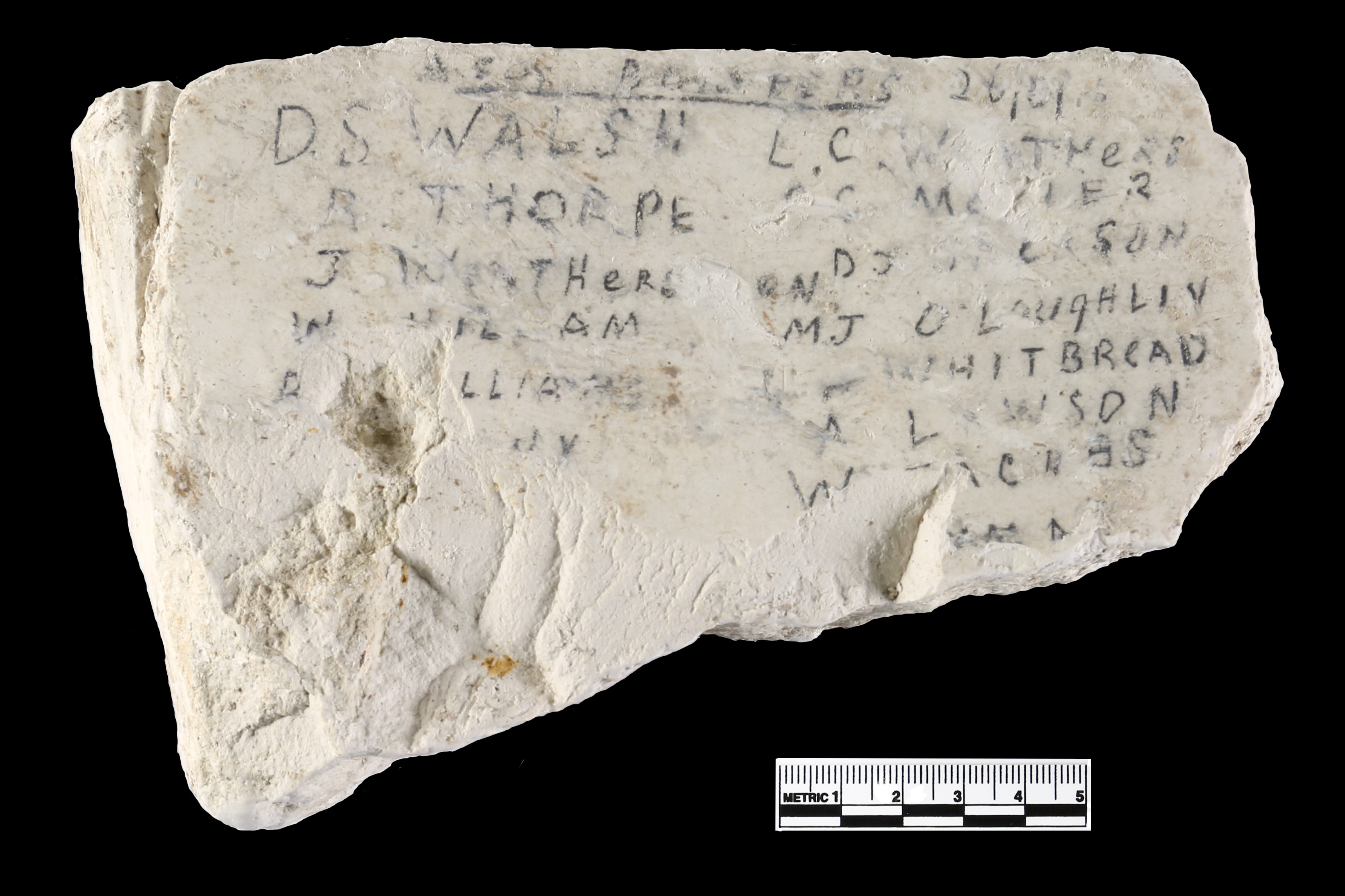

Soldiers training in the trenches have left their names to be found by the archaeologists. Over one hundred pieces of graffiti have been found written on and carved into the chalk of trenches, dug-outs and tunnels. The names include men who died, others who survived, decorated heroes and one deserter. The names come from Wiltshire men in the Wiltshire Regiment, from West Yorkshire coal miners, drafted in to work underground for King and Country, from the two Halls brothers who signed their names and wrote ‘Semper Fidelis’ (Ever Faithful) beneath. A poignant ‘RIP 19 Manchester Scouts’ may recall friends from pre-war Scouting adventures killed in action.

Soldiers from all over Britain wrote on the chalk and there are lots of Australian names too, recording men from the Australian Third Division, who trained on Salisbury Plain in 1916.

Steve Thompson, Senior Archaeologist from Wessex Archaeology said:

‘This project has been very important in bringing the names and faces of young men who volunteered to fight; without really knowing what they were letting themselves in for, back into the public eye. Many of these men paid the ultimate sacrifice after travelling half way around the world to train on Salisbury Plain before heading to the Western Front...

The fact it's the centenary this year of many of the bloodiest battles of the First World War and that we know men training here saw active service during these battles is all the more poignant. Each time a new piece of graffiti was uncovered or a new name revealed we would search for the individuals...

The First World War was a European and international conflict and our archaeological team comprises people from the UK, Italy, Spain, France, Poland and New Zealand. All these nations were greatly affected by the war and its aftermath. It is unlikely the archaeological team will ever get to take part in excavation such as this again – to excavate, almost in its entirety, an unknown WW1 training battlefield.’

Si Cleggett, Project Manager at Wessex Archaeology said:

‘Larkhill has been a once in a lifetime opportunity for our Wessex Archaeology teams, it has been a humbling experience for archaeologists to stand and read the names of young soldiers in the very spaces they occupied before embarkation to the horrors of the trenches.

It may be a cliché but, having stood in their footprints a hundred years after their days of training at Larkhill, we really will remember them.’

Australian Victoria Cross Winner Trained at Larkhill

Most exciting was the discovery of a chalk plaque inscribed with the names of Australian Bombers − soldiers specially trained to use hand grenades to attack and clear German trenches. One of the names is of Private Lawrence Carthage Weathers, who won the Victoria Cross in September 1918 for attacking a German machine gun post with grenades, capturing guns and taking 180 prisoners.

Martin Brown said ‘The chalk plaque and the large number of grenade fragments found show that Weathers learned his deadly skills here, on our site. He was one of thousands who learned soldiering at Larkhill.’

Trenches

The tunnels are beneath a network of trenches that recreate the battlefields of France. The archaeologists have cleared 8 km of trenches, working alongside bomb disposal specialists Bactec, as some grenades used in training were still live! They have found relics of training from food tins to ammunition and even a tin that once held an Australian brand of toffees, while a bucket had been turned into an impromptu brazier to keep men warm and boil water for all-important mugs of tea!

Hobbits and poets

JRR Tolkien was a young officer on the Somme. He lived in dug-outs and knew about the mines. The beginning of the Hobbit describes an idealised dug-out, while goblins, fight in the darkness and the fear of monsters living in the deeps (including fire-breathing dragons) have their origins in Tolkien’s war service.

War poet Wilfred Owen’s poem Strange Meeting talks of a dead soul wandering lost in the tunnels beneath the battlefields and reflects the poet’s fear of burial alive following his being trapped in a dug-out after an explosion.

By Martin Brown, Principal Archaeologist WYG