On Wednesday 18 April 2018, World Heritage Day, Phil Harding gave a lecture on Wessex Archaeology’s 2015−2017 excavations at Bulford, Wiltshire. The excavations were carried out ahead of development for the Army Basing Programme, a schedule of works involving the construction of new homes for British troops and their families returning from Germany. Phil’s was one of a series of lectures being given at Stonehenge to mark the 100 years since Cecil and Mary Chubb gifted the monument to the nation. As Bulford is some 4 miles away from Stonehenge, Phil’s brief was to ask if and how the Bulford site related to Stonehenge in any way. As a former employee at Stonehenge with a particular interest in Neolithic and Bronze Age landscapes, I was interested to hear the answer.

Phil presented to just under 150 people in a glass building on the first hot day of the year. The heat was uncompromising but Phil’s enthusiasm for the subject matter distracted the melting many and kept them engaged. The main focus of the talk was a series of 52 late Neolithic pits discovered at the site, with particular emphasis on their ceremonial rather than domestic character. Where most of the pits contained Woodlands style grooved ware pottery and broken or complete axes, some contained more unusual objects, seemingly deliberately placed. One such was a rare discoidal knife, the image of which elicited ‘oohs’ and ‘aahs’ from the audience and a knowing nod of the head from the speaker! Dating the pits from around 2950 BC meant they were in use at the same time as the first phase of construction at Stonehenge. Preliminary dating of two ‘hengiform’ monuments also uncovered during the excavations suggested that they too were in use from the late Neolithic c. 2450 BC, about the same time that the massive sarsens were being erected at Stonehenge. Brief accomplished: Phil had shown that whoever used these monuments and whoever placed deposits in the pits were almost certainly witnesses to at least two of the major phases of use at Stonehenge.

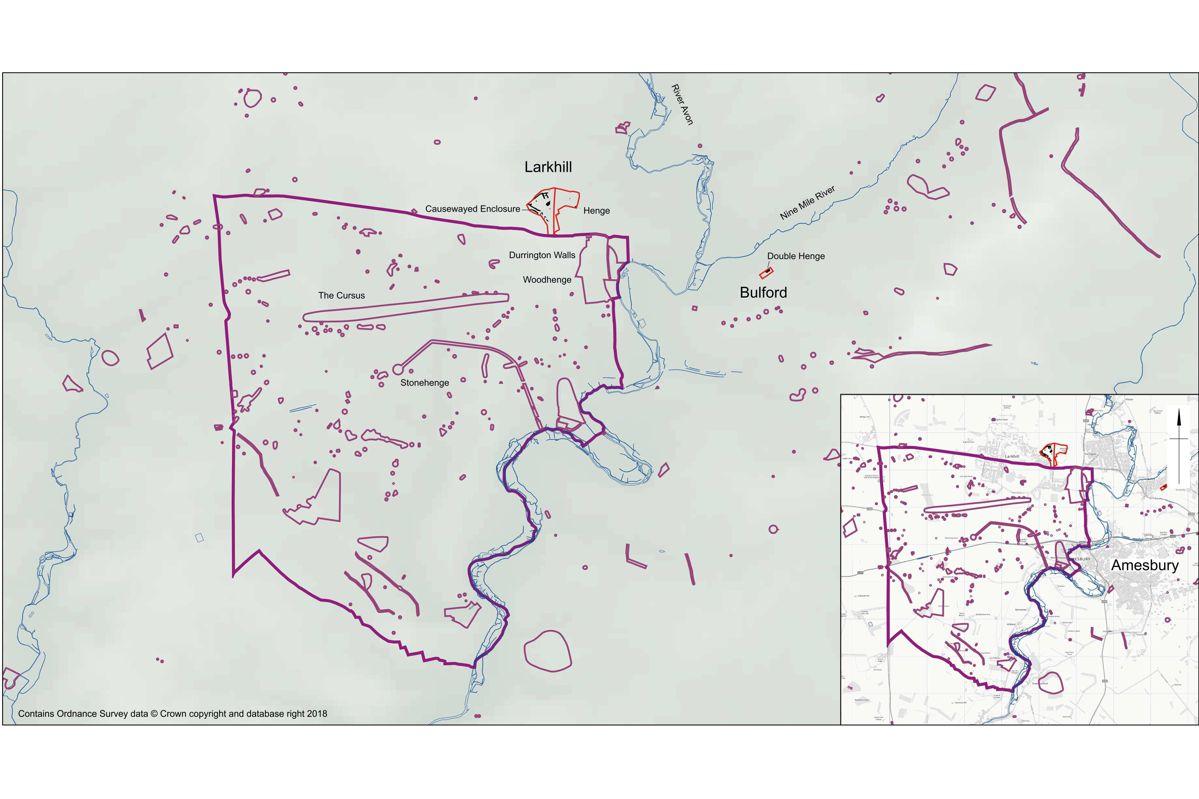

The results of the excavations at Bulford also highlighted that the ceremonial Stonehenge landscape must, more than ever, be seen to extend eastwards (and northwards with Wessex’s discovery of a causewayed enclosure at Larkhill) despite the arbitrary boundary of the World Heritage Site. The River Avon is a convenient natural eastern boundary, but it is not a representative one. The river has long been regarded as arterial in respect of the prehistory on the western side of it, but it is becoming increasingly apparent that the prehistory on the eastern side must be given equal regard.

Such limitations of the boundary of the World Heritage Site however, must be countered by the fact that this amazing site at Bulford, which also revealed an extensive Anglo-Saxon cemetery, might never have been exposed had it fallen within the boundary. Even if it had been, Phil might by then have long since retired – he admitted that the site had certainly pushed his retirement back! Doubly fortunate that it has then because Phil also acknowledged that it was one of the happiest and most rewarding sites of his career, not only because of the archaeology (and the fact it was on home ground) but also because of the team that worked with and for him. For me, it was reassuring to see somebody who has been in the industry for several decades (!) still so genuinely committed to the subject and still able to inform and entertain in equal measure.