On a personal level this is a site that I can’t forget in a long time, it was while digging here that I learned that my good friend Mick Aston had passed away, an unforgettable time.

It had all started so well, opportunities to undertake comprehensive studies of complete chequers are rare in Salisbury, but in 2013-14 the central part of Vanner’s Chequer was due to be infilled with houses. The development, extending from Bedwin Street to Salt Lane, also included land on the south side of Salt Lane, in Griffin Chequer. A documentary study was commissioned followed by preliminary evaluation and supplementary area excavations.

Vanner’s Chequer, one of the 20 medieval chequers in Salisbury, occupies the extreme north-east corner of the medieval city. Its location, on Bourne Hill, meant that it could not be included in the system of medieval water courses which flowed through the city. It was uncertain about whether this more peripheral location had developed at the same pace or had lagged behind other parts of the city. Preliminary trial trenches located 13th – 14th century rubbish pits and cess pits, which indicated that people had indeed lived along Bedwin Street from the foundation of Salisbury. Buildings on Salt Lane, in contrast, appeared to date from the 17th century suggesting a slight delay in the pace of development. The central part of the chequer, the ‘back-lands’, contained yard surfaces, outhouses and garden boundary walls.

These results were sufficiently encouraging to justify further digging. Sadly, no work was possible on the Bedwin Street frontage due to existing buildings, however, rubbish pits immediately behind these houses confirmed medieval occupation along the street. Access to the street frontage was better in the south west corner of Salt Lane where post holes, stake holes and pits preceded the construction of an impressive 13th-14th century house with chalk foundations. A series of well-preserved clay floors showed how the building had been renovated and subdivided many times during its life. Results at the east end of Salt Lane were totally different; the land had been quarried for clay to make daub for wattle and daub walls and also for flooring. Buildings were added in the 15th – 16th centuries when houses with low flint and chalk wall foundations were constructed. Water was supplied from chalk lined wells. Naish’s map of 1716 showed that Greencroft Street, on the east side of the chequer, remained unoccupied until much later, confirming the sluggish pace of development in this outlying chequer.

The central part of the chequer was divided up by a series of tenement wall boundaries, with pits, which included some with 15th – 16th century pottery, a date range that is poorly represented in the city. The ‘back-lands’ also produced a large, rectangular, chalk-lined cess pit, 1.8 m deep, a type of feature that we will look into, and consider the contents of in more detail, in a few weeks’ time.

Excavations subsequently progressed to a block of land on the south side of Salt Lane. Further evidence of medieval clay extraction was found, after which plots were maintained as cultivated ground or yards which were divided by tenement boundaries. Buildings were not erected until the 15th -16th centuries possibly in tandem with developments on the opposite side of Salt Lane in Vanner’s Chequer. Alterations were undertaken in the 16th -17th centuries when bricks were first used in construction with further rebuilding in the 19th century.

These combined excavations showed the beneficial results of examining peripheral areas of Salisbury as well as the central locations. They revealed the diverse nature of settlement and, most importantly, the variable speed at which the city limits developed, refuting any idea that Salisbury developed as a single event. Despite Mick passing I still recall this as a ‘happy dig’, the sun shone, and the developer always made sure that ice creams were stored in the fridge for a mid-afternoon break. A good way to run a dig!

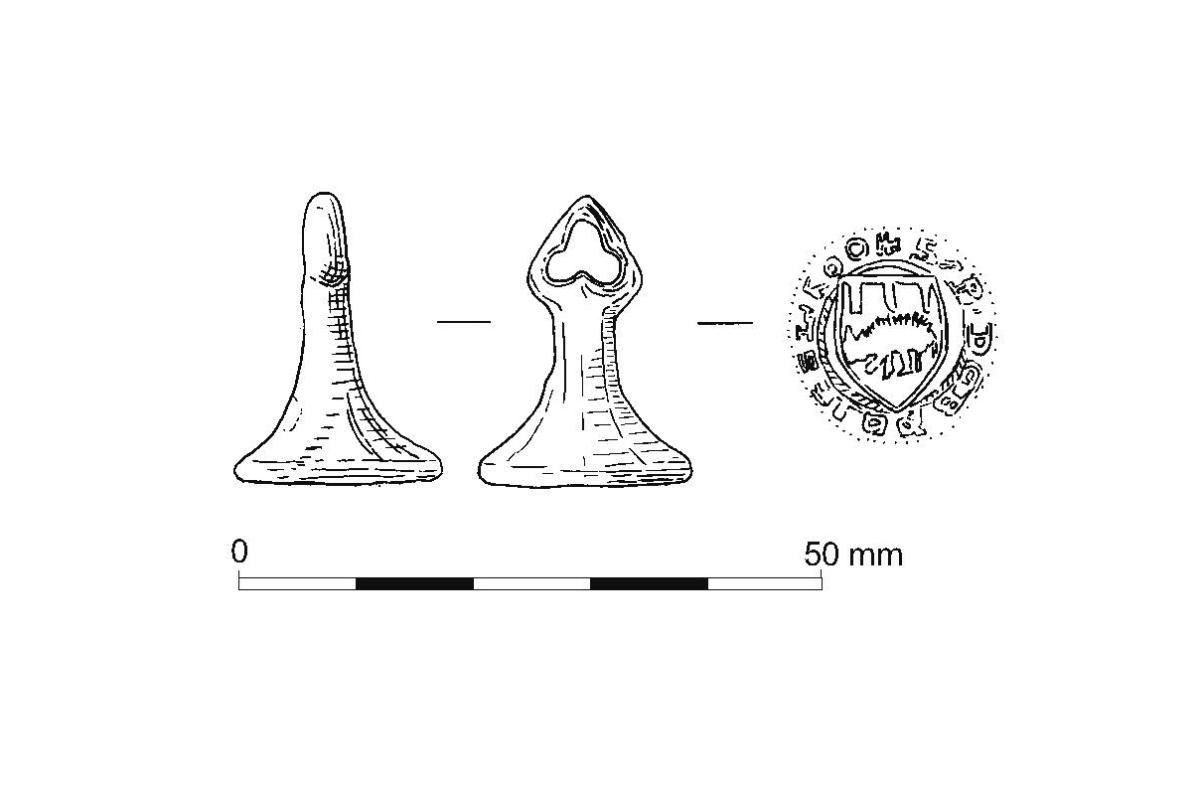

Most excavations produce individual finds that attract interest; Vanner’s Chequer was no exception. It included a 14th century seal matrix which, by its design, was probably a personal possession of a French or Norman heraldic gentleman who was visiting Salisbury.

We may never know how this loss occurred, but perhaps it resulted from the sort of entertaining activities which we can visualise associated with another find from the excavation, the spout from a puzzle jug. This vessel conjures up pictures of drunken revelry in 16th century Salisbury. Puzzle jugs were vessels, often used in riotous drinking games, which challenged an unsuspecting victim to consume drink by sucking the contents through a hollow spout which was connected through the rim and handle to the body of the jug. Given the use it is unsurprising that many got broken.

However, perhaps most interest should go to finds associated with William Morgan and James Skeaines, two 19th century clay tobacco pipe makers from Salt Lane. Their story is sufficiently interesting for us to break our journey and examine their lives in more detail next week.