Finally, after almost a year of journeying through the archaeology of Salisbury, we arrive at the end of our journey, but really the beginning; a point that encounters the first humans who lived in the area, occupying a river valley that now sits at the top of a hill. To solve this riddle, we need to explore a world that was then a very different place, unrecognisable from the location we know today. Perhaps the most familiar landmark would have been the River Avon, although not flowing then within its present channel or perhaps at its current leisurely pace.

Milford Hill ridge, framed by the inner ring road (left), the River Avon (bottom), and River Bourne (right), with Godolphin School at the centre

The location, Milford Hill, lies on a ridge overlooking the medieval city. The area coincides with some amazing archaeological discoveries, both in the annals of Salisbury and for me personally. It was in 1864, only five years after Charles Darwin had published his landmark volume ‘Origin of Species’, that Dr. Humphrey Blackmore, who we encountered last week at Churchfields, began to find and collect flint hand axes from gravel on Milford Hill. Salisbury was expanding and large residences appeared along this ridge on the east side of the city. Over 300 of these distinctive pointed or tear-drop shaped implements were found making it one of the most prolific sites of Lower and Middle Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age - 900,000 to 40,000 years ago) hand axes in Wiltshire. For a tool that remained in use throughout much of this period, the label ‘multi-purpose’, is most apt.

The summit of Milford Hill is covered by what is labelled rather grandiosely as Higher Terrace Gravel, although to the labourer it is simply stiff brown clay with mixed flints. Despite the large number of implements that were found, nothing was known to show how the gravel was formed or where the flint tools came from.

The conundrum remained unresolved until 1995 when I was part of an archaeological and geological watching brief at Godolphin School and construction of the Blackledge Theatre allowed the deposits to be studied in detail for the first time.

The Blackledge Theatre at Godolphin School

To the uninitiated there seemed very little to be seen; however, the geologist who was working with me, observed that in places minute horizontal beds of chalk with sand had been preserved in the deposits, which indicated that these fine layers had been laid down by a river, the River Avon. A line of pebbles, which continued unbroken through from the fine bedded layers into the clay, showed that the two deposits were the same thing.

The chain of events probably happened during one of the ice ages which we know occurred in geological time across the world. Wiltshire was never actually covered by ice; however, the area was permanently frozen for long periods of time. Periodically the climate warmed sufficiently to release large volumes of fast flowing water into rivers. It also thawed the upper surface of the ground which allowed large amounts of muddy chalk and flints to slip down the valley sides, over the frozen ground below, to the banks of the river. Anyone who has slipped on ice knows how unstable frozen slopes can be. Traces of human activity, including hand axes, may have lain abandoned on the ground for long periods of time, been included in the sludge and incorporated into the flood plain as the river eroded its banks. We still do not know precisely when this occurred, but a time approximately 300,000 years ago seems likely. Since then the chalk, which was once a major component of the gravel, has largely dissolved, erasing traces of the water-lain bedding, leaving clay-rich gravel.

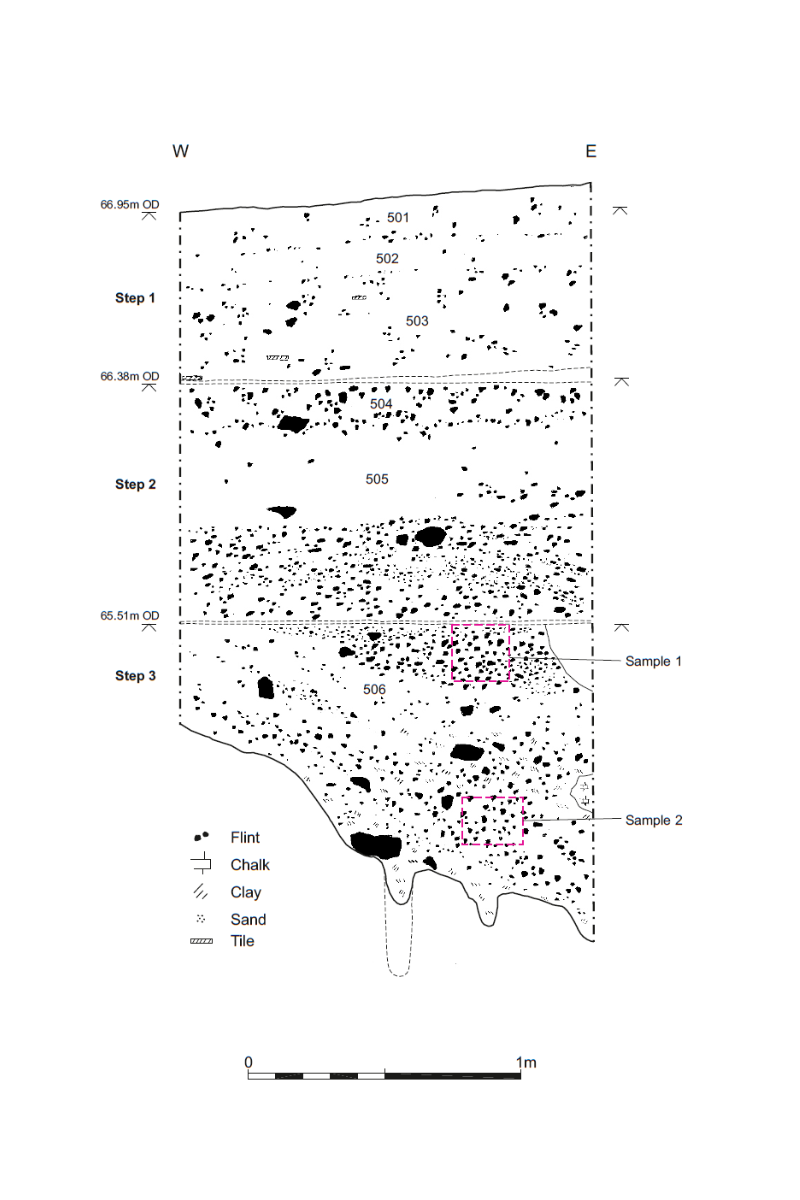

Drawn section and photograph of the Milford Hill gravel at the former Youth Hostel

Dramatic changes have also occurred in the landscape; not only has the river cut down to its present course, removing traces of the former valley, but we now appreciate that the land has continued to rise, resulting in this remnant of the former flood plain now lying at the top of the hill.

These observations helped to resolve the story of Milford Hill; however, relatively late on in the project at Godolphin School I was watching a machine digging a foundation trench when I spotted a large flint object that demanded to be investigated. True enough it was a hand axe, probably the first to be discovered on Milford Hill for over 100 years. Discoveries like that do not get much better.

Phil's lucky find!

Subsequent projects at Godolphin School (WA Project 57850 and 57851) and elsewhere on Milford Hill at 37 Fowler’s Road (WA Project 79780) and the former Youth Hostel (WA Project 100171), where work is on-going (WA Project 100172), have established the extent of the gravel at the east end of the ridge. Sadly, no additional hand axes have been found.

Excavations at the Godolphin School (left), near the edge of the gravel, and at the former Youth Hostel (right), where the deposit is thicker

These small-scale projects have benefitted from specialist geological input to show how the vastly different landscape has evolved. The archaeologist adds human detail, which was created by some of the earliest occupants of Britain. As a child and apprentice archaeologist I was fascinated by stories of ‘cave men’ and dreamed of finding a hand axe. Working on Milford Hill not only helped contribute to the story of the city in which I live but also achieve that personal goal.

By Phil Harding, Fieldwork Archaeologist

We hope you’ve enjoyed discovering Salisbury’s archaeology as much as we’ve enjoyed sharing it! Could you help us to continue sharing the city’s history with our community film, Salisbury Uncovered? Find our more here!