We now move a short distance to our next destination, three tenements, Nos 47, 49 and 51 Brown Street, where excavations sampled both the street frontages and the ‘back-lands’. The site functioned as a car park but featured a very distinctive Salisbury backdrop which has also subsequently disappeared allowing the land to be redeveloped.

The project included limited documentary research, which provided written hints of former occupants and high-lighted how documentary evidence, much of it often untapped, can add colour to the archaeological results. All three buildings were demolished in 1972; Nos 47 and 51 Brown Street were both 18th-19th century brick buildings, but No 49 Brown Street was listed by the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments as a two-storey, timber-framed 16th century ‘cottage’, with a 19th century service wing.

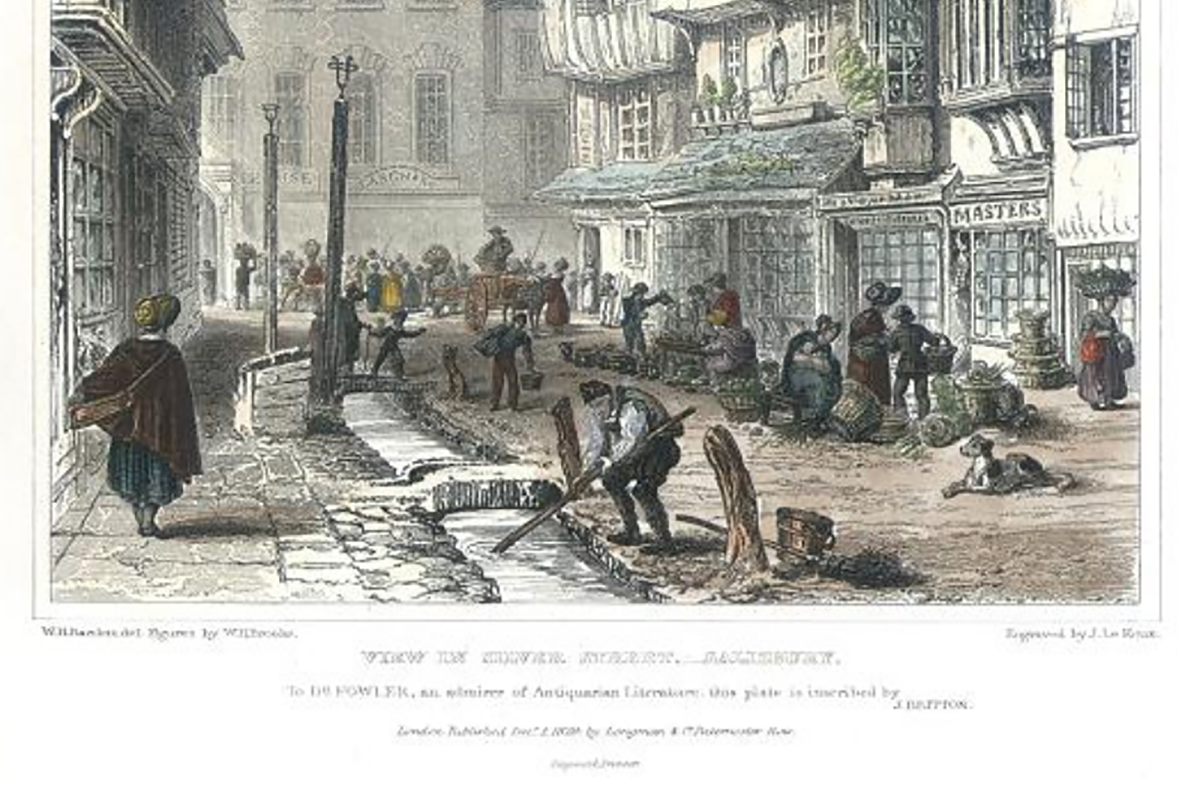

The project also exposed the upper courses of the Town Ditch, which formed part of Salisbury’s network of medieval water channels. It seems strange but this limited examination still constitutes the most thorough investigation of this crucial part of Salisbury’s past. The Ditch had been constructed initially using Chalk and Greensand with subsequent repair using bricks and was probably of similar appearance to the channel shown in a painting by W.H. Bartlett of Minster Street in 1829.

Right: View in Silver Street, Salisbury 1829 [detail], engraving by J. LeKeux after W. H. Bartlett and W. H. Brooke (courtesy of antiqueprints.com)

Despite the fact that the former building on No.49 had occupied the site since the 16th century, archaeological layers and buildings were thought to be better preserved at 51 Brown Street and this tenement served as the reference point for adjoining properties. Occupation at No 51 began with a scatter of post and stake holes which were covered by the earliest recognisable floor, which contained small amounts of 13th and 14th century pottery. The earliest structural evidence was defined by flint foundations which created a building of approximately 30 sq m, similar in floor area and design to the adjoining house at No 49 and repeating the pattern we saw at the Anchor Brewery. Passageways allowed access to the ‘back-lands’.

Peg tile hearths were placed in the centre of the room on clay floors. Layers of dark brown/black charcoal-rich debris suggested that occupants preferred to repair or patch existing floors rather than install new surfaces.

Subsequent rebuilding and renovations at 51 Brown Street were undertaken later in the 13th or 14th century. These alterations included installation of a partition to sub-divide the principal room into separate living and sleeping accommodation, a design feature that we saw at the Anchor Brewery in the period between 1350-1450. The central hearth was replaced on two occasions while the floor was also renewed. No comparable phases in the period 1350-1450 were identified at Nos 49 or 47 Brown Street, although it is likely that undocumented internal modifications were made.

Note the scaffolding around the spire of Salisbury Cathedral in the background (left); this scaffolding remained in place during renovations of the spire between 1987 and 1990

Significant changes occurred at Nos 51 and 49 Brown Street during the 15th-16th century, most notably repositioning the tile hearth against a wall. This development coincided with increased use of chimneys across Britain after 1450, encouraging the installation of upper storeys. A chalk floor at No 51 represented the final earthen floor, possibly indicating the appearance of wooden floors. Significantly, this major episode of redevelopment probably incorporated these features at No 49, the building demolished in 1972.

Small trenches were dug in each tenement to sample the ‘back-lands’. They found traces of service wings and out houses, some possibly connected to the main residential range, with yards, wells and cesspits. At No 51 a series of possible late medieval chalk block wall foundations were later rebuilt to include a chalk lined cesspit. We have seen elsewhere that cesspits were certainly in use by the 15th -16th century and were often set back from the street against tenement boundaries, although others were placed nearer to the street frontages. An additional out-building with flint foundations adjoined the Town Ditch at the end of No 51. The absence of bricks in its construction suggested a late medieval or early post medieval date.

The excavations high-lighted the ever-changing character, appearance and use of the ‘back-lands’ and their occupants. The discoveries included four square or irregular pits, at No 51, which all contained horn cores, and may have been connected to John Leminge, a skinner, who occupied the premises after 1628. One of the pits was located within the front room of the house suggesting a period when the plot may have been vacant and awaiting redevelopment.

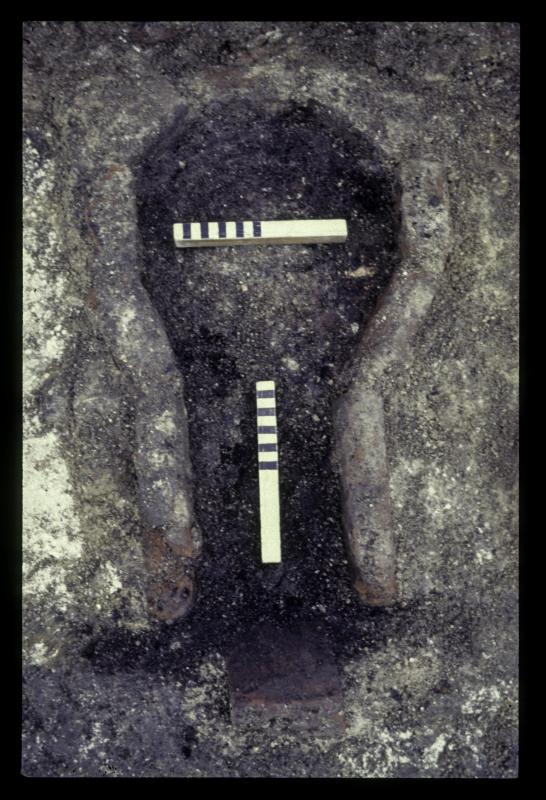

Four small undated brick-built kilns or ovens were also found at Nos 51 and 49 Brown Street; the use of brick suggesting a date after 1600 when bricks became more common. Finally, a triple-celled structure was built using chalk blocks at the rear of 51 Brown Street. These possible fulling tanks may have been linked to Thomas Spencer, a felt maker, whose lease of the property lapsed in 1675.

This excavation not only produced interesting archaeological results but also introduced so many young people to archaeology. Education and outreach is now a vital part of many excavations, but at the time was innovative; how many people shown in this photograph will recall that day, I wonder?