Over the last four weeks I have had the incredible experience of working in the Geomatics department at Wessex Archaeology. I have been consistently amazed at the huge number of academic disciplines archeology draws from. Indeed, I have greatly enjoyed taking ideas from disparate areas of materials science and biology to answer a seemingly unrelated question.

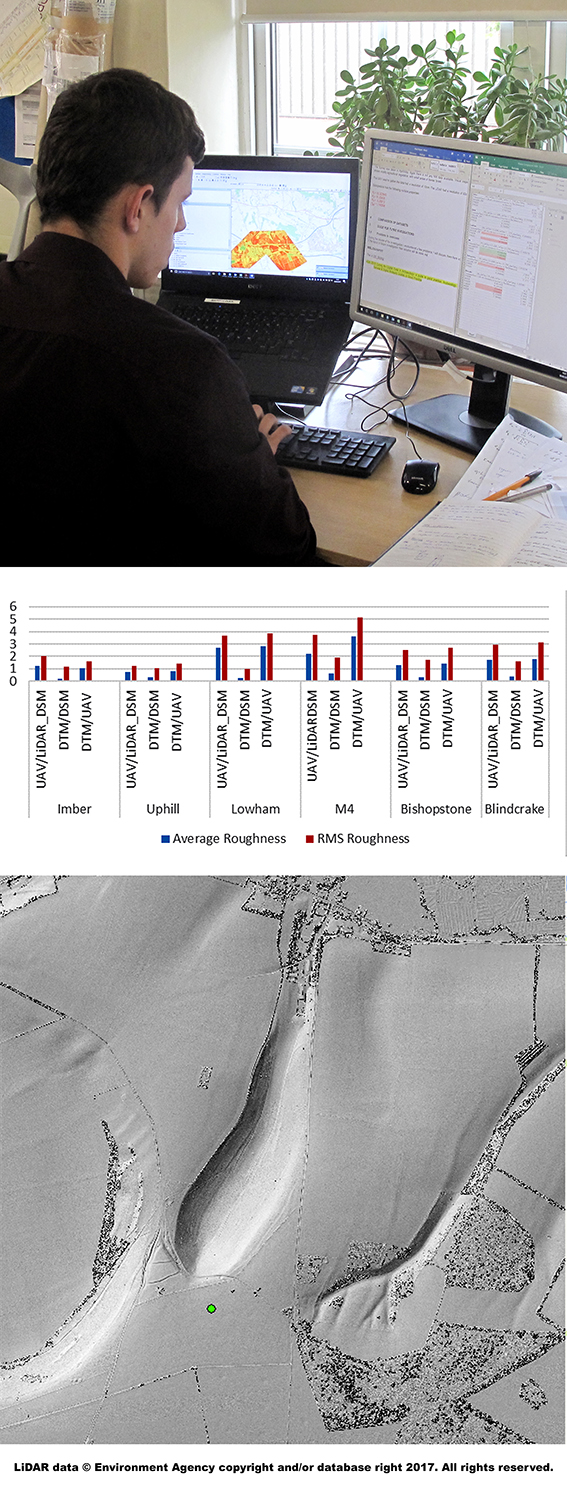

The purpose of my project was to give a comparison between the use of lidar (light detection and ranging) derived datasets and the use of UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) derived datasets in the application of discovering archaeological features. This was with the aim of better understanding the limitations of using UAVs.

There are two main ways of generating elevation models from the earth’s surface. The first involves reflecting laser pulses from an aircraft off the ground to measure how far the aircraft is from the ground at every point. The second uses multiple aerial photographs to generate a 3D model of the ground.

Data of both kinds was available from 6 different locations across the country. I numerically compared them to show how similar UAV is to lidar. This was done by subtracting one dataset from the other to show how much they differ. Statistical formulae are also applied to the same end.

I suggested several factors as the cause of these differences including:

• The time of year the datasets were collected;

• The amount of vegetation present;

• The general roughness of the surface;

• The resolution of the lidar and UAV data.

I quantified these factors, using a range of techniques, to work out which have the greatest effect on the difference between the two datasets.

My investigation has revealed that differences in elevation datasets are independent of all the factors listed above. This is a surprising conclusion. The differences are too large to be random, so, either the data sample was too small to show any correlation or there is another factor that determines the location consistency. Both possibilities provide exciting opportunities for future investigation, and if this project has done nothing else it has laid out the methodology for doing that.

I would like to thank Wessex Archaeology for this opportunity, in particular Rachel Brown for her organisation and kindness, Richard Milwain for providing the project and supporting me throughout and the Wessex Archaeology Geomatics department for being friendly and accommodating. I would also like to thank Ken Lymer for his assistance in producing a poster. In addition, I would like to thank Sue Diamond, Gillian O’ Carrol and Sam Wenman for coordinating my placement. Lastly, I would like to thank the Nuffield foundation for their financial assistance.

By James Thorn