Historic England often turns to Wessex Archaeology Coastal & Marine when it needs archaeological advice about whether to protect important historic shipwrecks. Our advice has led to the protection of many marine sites, including those as diverse as the 17th-century Swash Channel wreck and the First World War U-boats U8 and UC70. The advice we deliver is based upon both desk-based research and diving, and geophysical fieldwork, often carried out with the avocational archaeologists and divers and other members of the public that have reported the wrecks to Historic England.

Last year we investigated a number of previously unknown wreck sites reported to Historic England following a routine hydrographic survey in the South East. One of those wrecks has proved to be particularly interesting.

It is the wreck of a three-masted wooden sailing ship of the 19th or early 20th century. We don’t know what it was called or exactly when it was lost, but we do know that it had three masts because the lower sections of two of them are still in place and because their positions suggest that there was a third. The rudder is still attached to the stern, part of the bow sprit is still in situ and some of the deck is in place. This level of preservation is exceptionally rare and I have personally only seen it as a diver twice before, during our investigations of the warship Stirling Castle, lost in the Great Storm of 1703, and an unidentified wooden collier ‘GAD 25’ on the Goodwin Sands. In all likelihood the wreck has been buried in sand for most of the time that it has been on the seabed and has only recently been exposed by erosion.

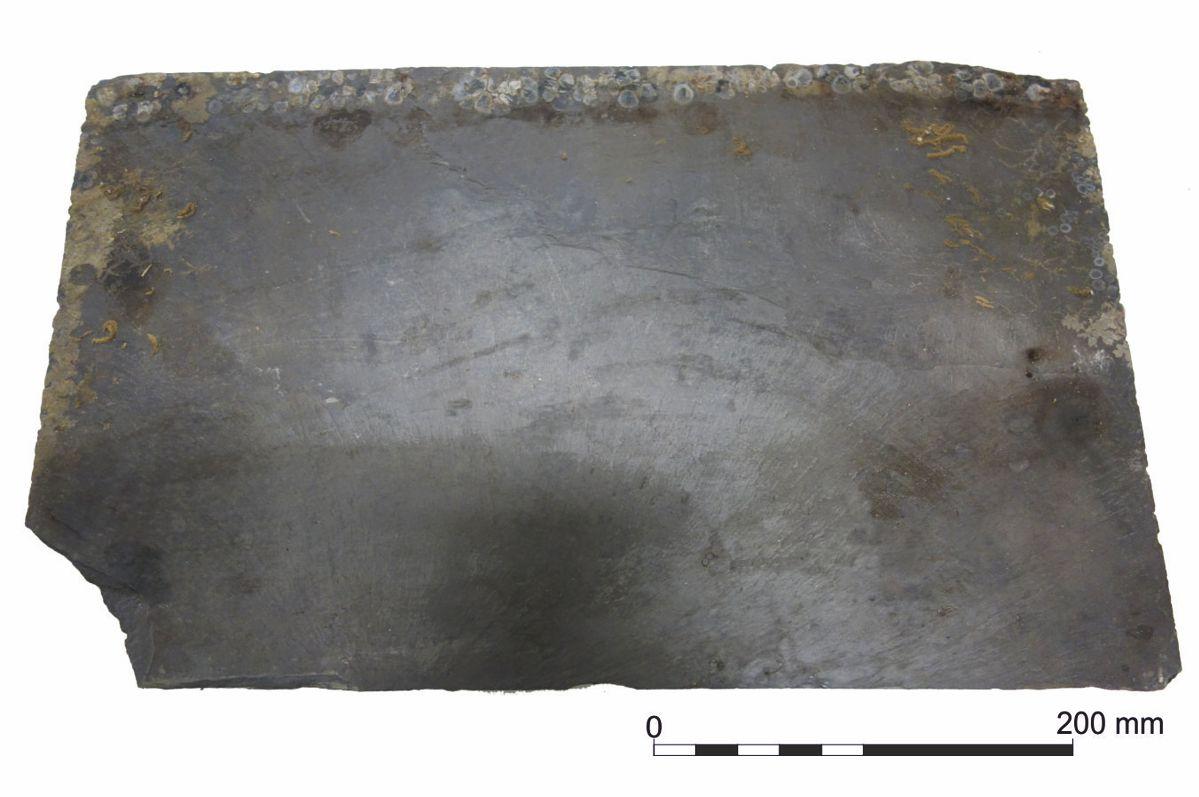

However, this ship was not a warship or a collier. Instead it was a slate carrier and its hold is full of closely packed roof slates. These appeared to be Welsh sizes but, with the help of Dafydd Roberts and his colleagues at the National Slate Museum in Llanberis, Wales we have discounted that. Instead we believe that they are almost certainly Cornish. This has been confirmed by George Harrison, the manager of Delabole Quarry, then and now the historic centre of the Cornish slate industry. He has told us that the sample slate we recovered that he has examined has the physical qualities of Cornish slate and certain qualities of Delabole slate, including the dark bandings across it. It was probably dressed with a rotary knife rather than by hand. This dates it no earlier than the early 19th century and Mr Harrison thinks that it was probably made about 1880.

The bowsprit, and a roof slate from the wreck

Slate at that time was usually shipped via the North Cornish harbour at Port Isaac. From 1893 the railway reached Delabole and most slate after that date was moved by rail, so our mystery ship is likely to pre-date the arrival of the railway. We are currently working with staff at the NRHE to identify the ship and hope to bring you news of our progress shortly. In the meantime, DCMS is considering whether to protect the site.

If you are interested in the Cornish slate industry and want to know more about Delabole, a book by Catherine Lorigan about the very long history of Delabole is available for purchase from the quarry.

By Graham Scott, WA Coastal & Marine & Wessex Archaeology West