On the morning of the 31 May 1878, a squadron of three of the Imperial German Navy’s latest ‘ironclad’ warships found itself off Folkestone in calm seas. The ships were shortly to play their part in the great political rivalries of the major European powers and were bound for the Eastern Mediterranean. The show of force was intended to protect Germany’s geopolitical interests in the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War.

Unfortunately for them, the Straits of Dover were as busy then as they are now. Manoeuvring to avoid an approaching sailing ship went wrong and the captain of the recently commissioned Grosser Kurfürst found himself turning across the bows of another ship in the squadron. Despite violent evasive action the Koenig Wilhelm crashed into the side of the other vessel, its specially strengthened ram bow ripping away armour plate and gouging a huge hole in its side. The sea flooded in and within a few minutes the Grosser Kurfürst turned over and sank, drowning hundreds.

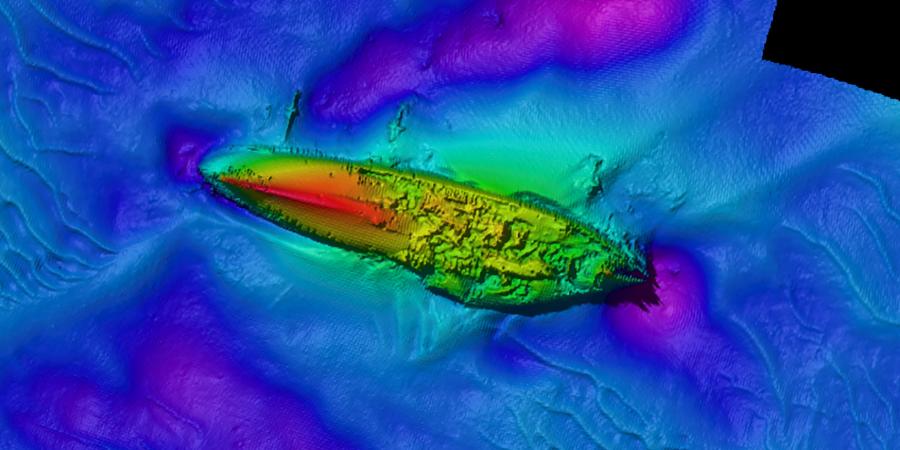

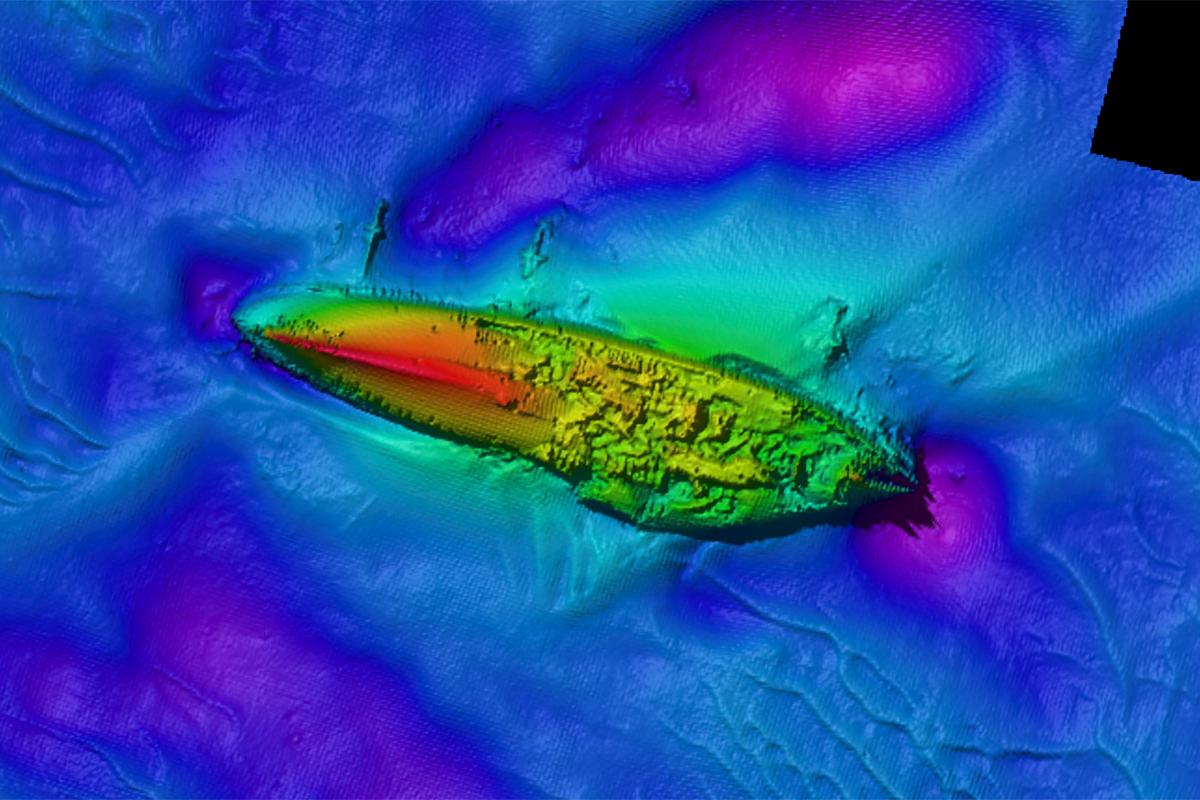

On Friday, subject to weather, a Wessex Archaeology dive team will begin a non-intrusive survey of the wreck of the Grosser Kurfürst for Historic England. Using data supplied by the UKHO, our marine geophysicists have processed this multibeam sonar plan-view image of the wreck. Although it is partially collapsed, you can see that the hull is upside-down, just as the historical records suggest the ship sank. However, this data does not tell us everything and, using a hand-held imaging sonar and sharp eyes, our divers will be trying to answer a number of questions about this large wreck.

As an ‘ironclad’, the ship is from a revolutionary period in naval warfare in which navies moved from reliance upon wooden to armoured ships and which saw the emergence of the forerunners of the great Dreadnought battleships of the First World War. It was a highly experimental time that briefly saw the return of the ancient ram, but ended with the dominance of armour plate and the big gun. It is rare for European ocean-going ironclad warships to be studied archaeologically, so we hope that this work will contribute to our knowledge of this fascinating period in naval history. Watch out for Facebook and Twitter updates in which our lead archaeologists Graham Scott and Paolo Croce pose, investigate and hopefully answer questions about the wreck.