On 20 April 2017, an Edward I long cross silver penny was found during the excavation of the former site of the Cock, a 19th-century public house, just off Hollis Croft, Sheffield. The penny is remarkable, not just with regards to its age and relative scarcity but also to the context in which it was found.

Wessex Archaeology Sheffield has been carrying out excavations at the Hollis Croft site ahead of a major urban residential development. This work has targeted several potentially interesting areas; these include examples of back-to-back housing typical of 18th-century urban development in Sheffield and two public houses, the Cock and the Orange Branch, which can both be seen clearly on several 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps. Sheffield has been inhabited since at least the mid-11th century, and is recorded in Domesday in 1086. The Hollis Croft area was, for much of the medieval period, left open and known as Town Field and by the early modern period had been enclosed and subsequently comprised several closes and crofts. It is from these enclosures that many of the current streets, first laid out in the early 18th century, take their names. Over the course of the following two centuries ‘The Crofts’, as the area would come to be known, was to become a centre for manufacture and trade, particularly that of the metal trades such as cutlery. The scale of this industry would continue to increase until the widespread decline of manufacturing in Sheffield during the late 20th century. The Hollis Croft area came to be largely the property of one company, Footprint Works, which was established in 1944.

During the 1960s the site was developed, with the construction of a Footprint Tools building. It was considered likely that this development would have destroyed any archaeological remains, however the excavations carried out by Wessex have demonstrated that this was not the case. The site has so far produced a variety of finds, although the lack of any obvious residential occupation of Town Field during the medieval period means that medieval artefacts have proved few and far between; the majority of the archaeological material identified dates from the site’s industrial occupation. Amongst this material there were a large number of leather shoes and a substantial deposit of decorated but unfinished bone handles, reflecting the high density of craftsmen and manufacturers listed as having been resident in Hollis Croft in the late 19th-century Trade Directories.

The first reference to the Cock Public House, where the coin was discovered, is in the Henry & Thomas Rodgers Sheffield & Rotherham Directory from 1841. The pub is also shown on an 1853 Ordnance Survey map and its name – the Cock – probably comes from the stop-cock used on contemporary beer casks.

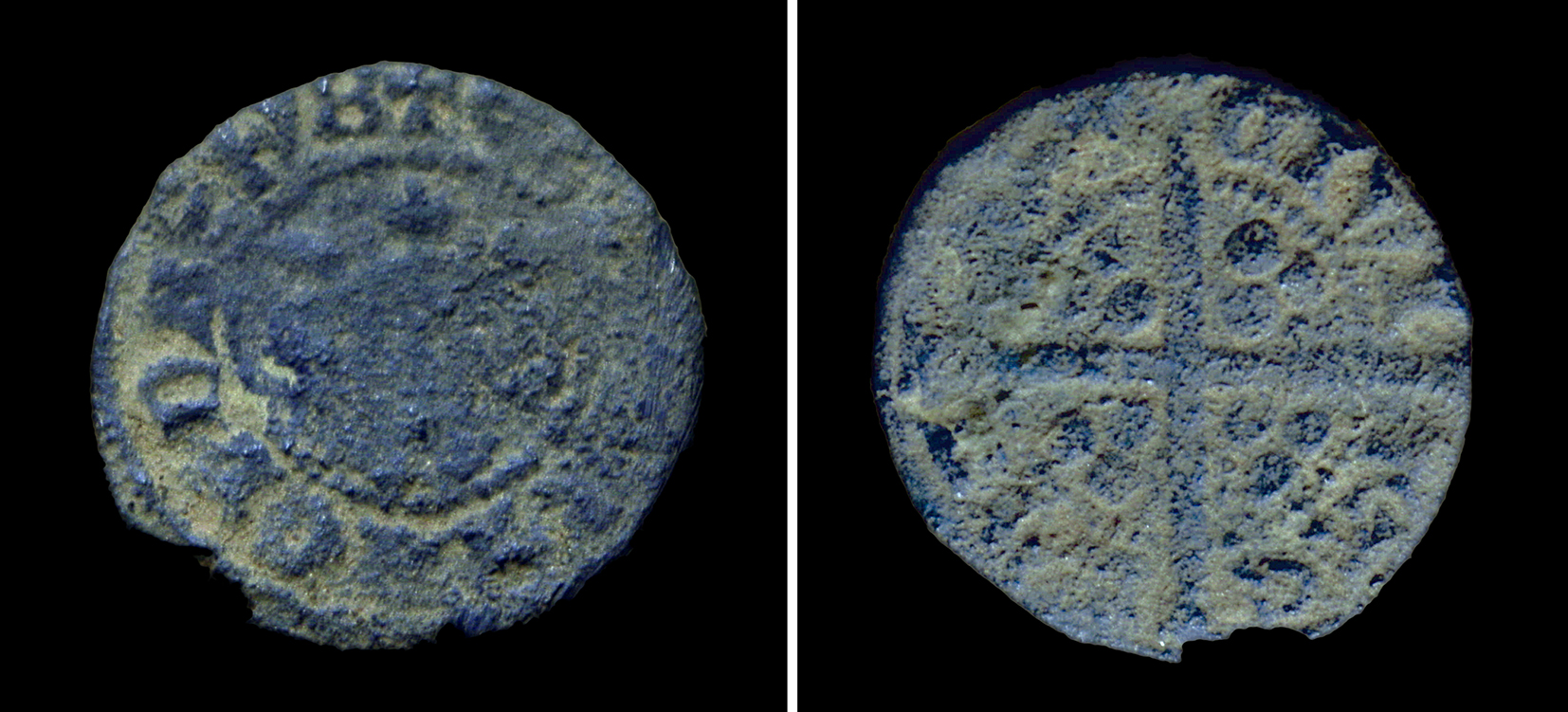

The aim of the archaeological investigation was to enhance the understanding of the early phases of the construction of this part of the city to compliment the extensive late 18th- and 19th-century archival evidence. An awareness of earlier phases is central to Wessex’s methodology so the coin clearly holds significance. But why was a medieval coin found in such a late context? The rarity of the find and the location raised immediate questions of authenticity and some of us thought the coin was a fake. Visualisations of cheeky Yorkshire pub locals with tricks up their sleeves and fakes in their pockets are enticing for a born and bred Sheffielder such as myself. However, when inspected by experts, the authenticity of the coin was confirmed. To further determine the coin was the real thing, its composition was tested. It was found to be 93% percent silver with small traces of iron, gold and magnesium. It has therefore been identified as a silver penny from the reign of Edward I, with a bold long cross embossed on its reverse and the face of the king on the obverse.

The obverse face of the penny showed a more realistic portrait of the monarch than had be previously been usual and also depicted him facing forward as opposed to in profile. The reverse showed a long cross, equal armed and stretching from one edge to the other. We know that any silver penny with these attributes must have been minted within the 39-year reign of Edward I, more than five centuries prior to the establishment of the Cock Public House.

Edwardian coins are important when studying the economic history of later medieval England. Monetary denominations had changed very little in the five hundred years prior to the coronation of Edward I in 1272AD but he would soon make some sizable reforms. The long cross was originally introduced as a device to make more difficult the clipping and splitting which had previously been used to divide the penny into the literal half penny or farthing. Edward I also introduced other new coins, the groat, halfpenny and farthing, further reducing the need to physically divide larger denomination coinage. The new coins strengthened England’s foreign trade power and the penny proved especially successful because of its high silver content and uniform weight.

The coin found at Hollis croft has a chip on the lower side slightly to the left when examining the obverse. The face of Edward I is badly worn, however the reverse long cross and accompanying pattern is clear. The only link the site has with the medieval period is that this area of Sheffield followed the old field boundaries laid out following the enclosure of Town Field. Hollis Croft’s layout is the only clue to the continuity of the inhabited area from the reign of Edward I and the minting of the penny, to the establishment of the Cock public house in the 19th-century.

It remains unlikely that the coin’s context will be further illuminated by the planned excavation. The coin could have been dropped by an absent mind in the medieval period, churned up by ploughing, finding its way into material which was reused when the pub was erected. However, firmer conclusions remain out of reach. Although the coin confirms to a degree that the site was being used in some form during the medieval period, the nature of this link is unknown and any more definitive historiography would be speculation.

By Oisin Mercer Archaeological Technician