The diversity and domestication of Neolithic pulses(s)

22 May 2022 was International Day of Biological Diversity so, as an Environmental Archaeologist here at Wessex Archaeology, I thought I’d share a bit of past diversity with you all. Biodiversity is the ‘variety and variability of life on Earth and how it changes from one location to another and over time’. So, with that in mind, I’m going to tell you about pulses (Fabaceae).

When and what?

Pulses are harvested from leguminous plants such as lentils (Lens culinaris), common peas (Pisum sativum), broad beans (Vicia faba) and many others. The Neolithic era spans 4000 to 2200 BCE (Before Common Era) in the British Isles, but spanned from 10,000 to 4,500 BCE in the Near East, where many different pulses we see in the supermarket today were first cultivated and domesticated.

This period saw many changes to everyday life with the introduction of arable farming, pottery production, house building, and woodland management, to name but a few. As part of the ‘Neolithic Revolution’, we see both cereal plants (particularly wheat (Triticum species) and barley (Hordeum species) and pulses start to be cultivated and deliberately selected for useful traits.

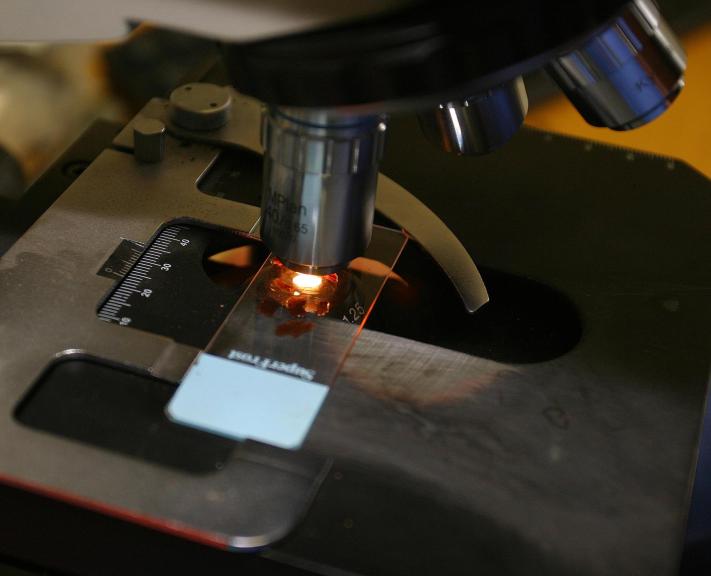

Above: Neolithic site at Boscombe Down where they would likely have harvested pulses and Environmental Archaeology analysis

How?

Despite early disagreement it is now widely accepted that cereals and pulses were domesticated in the same way. So, what are the differences between wild and domesticated pulses?

-

change in size (modern pulses are larger than their wild cousins, bigger pulses = more food),

-

the way they disperse their seeds (the seed pods of cultivated pulses burst slowly or not at all, keeping the pulses inside the pods so they can be more easily harvested later),

-

easier to process (thinner coats so water can get in and seeds can germinate quicker).

However, the size increase between wild and domesticated pulses is very difficult to observe archaeologically, added to which pulses can vary dramatically in size and shape within the same pod. Unfortunately, this means that the remains of early domesticated pulses can be easily confused with wild varieties in the archaeological record.

Above: A Neolithic antler pick,

Why?

Fertility

Pulses are ideal companion plants to wheat and barley crops because pulses add nitrogen to soil so they’re great for soil fertility. This means they can be used in rotation with arable crops to ensure continued growth and harvests.

Nutritious and delicious

Lentils, common peas, broad beans, and chickpeas are the principal pulses of Old World agriculture (the Old World encompasses Asia, Europe, and North Africa), but not all of them made it into the UK during the British Neolithic, many pulses were imported into the UK much later. For example, some of the earliest finds of lentils in the UK derive from charred specimens identified in Roman (1st to 2nd century AD) sites in London and Kent, where they were likely imported via the Mediterranean.

Some pulses are now used as a meat substitute (for example, lentils and chickpeas) but all are high in protein and nutritious. For instance, grass pea is drought tolerant and survives on poor soil: today it’s hailed as a lifesaver in drought ridden countries in times of famine.

Above: Lentil (charred archaeological examples), Pea, Broad beans (various varieties). Image credit: Dr. Ed Treasure, Environmental Archaeologist

Fodder

Many pulse crops can be grown as animal food (fodder) or as a part of human diet. However, during famines or periods of ecological stress (when there may have been a greater need to eat pulses) the difference between food and fodder could be interchangeable. Some of the most common pulses used as fodder crops are vetches (Vicia spp.).

Above: Common vetch (Vicia sativa)

Fun fact - Pulses have been identified among the foodstuffs left in the tombs of Egyptian kings.

In short, as with so much of archaeology, we need to have more examples to analyse!

By Liz Chambers, Environmental Archaeologist

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Fernand Lambein et al, G. Ladizinski, Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf whose works were consulted for this blog.