In the shadow of a nuclear power station, lies one of the UK’s most mysterious and intriguing wreck sites. On the seabed close to the former medieval town of Dunwich lies evidence of what was probably a 16th century ship carrying bronze cannons. This is the Dunwich Bank Wreck, one of a small group of historic shipwrecks protected under law as nationally important archaeological sites. Historic England considers this site to be at risk, partly because bronze guns are valuable and vulnerable to theft. It has therefore put in place a conservation management plan for the site.

We do not know where this ship came from or where it was going. We haven’t even found clear evidence of the ship itself yet. One of the bronze cannons has been recovered and it is on display in Dunwich Museum. The markings on the gun tell us that it was cast by a gunfounder called Remigy de Halut, probably in the late 1530s. His foundry was in Mechelen in Flanders, then a wealthy and technologically advanced region that was famous for gun making. The cannon expert Rudi Roth speculates that it is even possible that the Dunwich Bank ship was carrying a cargo of guns being imported for Henry VIII, a forward-thinking and enthusiastic collector of artillery.

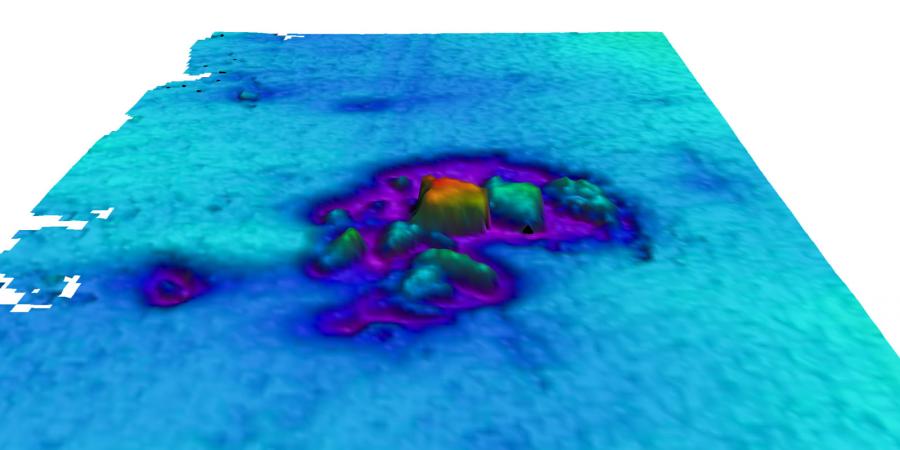

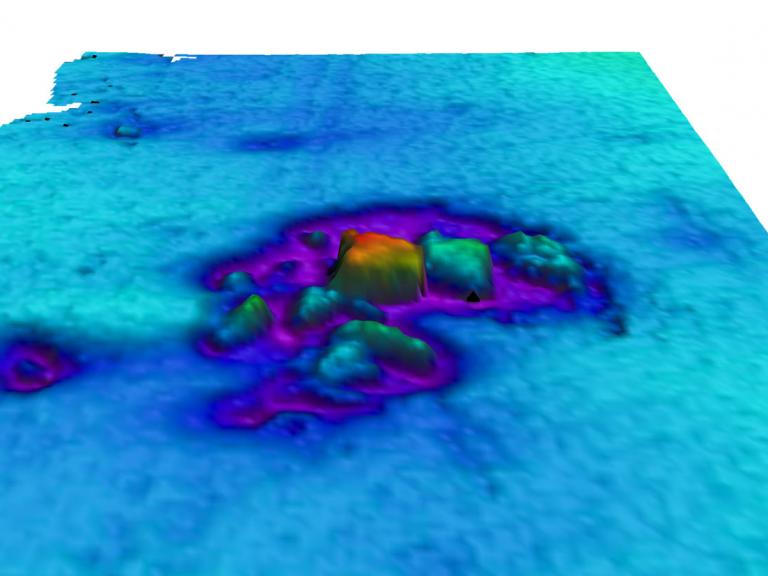

Multibeam echo-sounder image of the Dunwich Bank wreck site, and the previously recovered cannon

Wessex Archaeology has teamed up with the avocational divers who are investigating and safeguarding the wreck. After having been buried for a while, probably due to coastal erosion caused by winter storms, the site has again emerged. Funded by Historic England, this week we will be using the opportunity this presents to carry out a short excavation to try to find evidence of the ship itself. We will also be looking for finds that might help us date when it was lost, where it had come from and perhaps even where it might have been going and for whom.

As one of the site’s original discoverers and investigators, local avocational archaeologist Stuart Bacon would testify, diving and working on the site is extremely difficult because it is normally impossible to see anything underwater. There is so much silt and other ‘particulate’ in the water, that a diver cannot see anything at all, just blackness. Let go of something you recognise and turn around and you can be completely lost. Everything that archaeologists rely on to work on land sites, such as being able to see what you digging and being able to look up and immediately understand where you are is absent on this site. Instead, the diver archaeologists must work by touch during the brief periods when the tidal current slows down enough to enable then to get in the water and work.

This is not the first time we have worked on this fascinating but immensely difficult site. However, it is the first time that we have been allowed to dig and we do not know what we are going to find. Will we find evidence of the ship? Will we recover any finds that allow us to date it? Will we find out more about the guns and perhaps even where they were going? Watch out for further news as the excavation progresses…