Ancient skeletons reveal the history of worm parasites

We’re delighted to announce our involvement in a recent multidisciplinary research publication, ‘Reconstructing the history of helminth prevalence in the UK’, on the development of intestinal worms. The new collaborative research has been published in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

Wessex Archaeology Senior Environmental Archaeologist, Inés López-Dóriga, has recently participated in new research with the University of Oxford’s Departments of Biology and Archaeology. Inés coordinated preparation of environmental samples for research use from a diversity of Wessex Archaeology sites.

This new parasite-based approach to interdisciplinary research will allow greater insight into human health from the Prehistoric to the early Victorian periods. We look forward to seeing how this research develops as collaboration continues between a combination of archaeologists, historians, parasitologists, and biologists.

Inés López-Dóriga, Senior Environmental Archaeologist with Wessex Archaeology, said:

‘Samples taken during archaeological fieldwork investigations by Wessex Archaeology has helped research the history of human worm parasites in Britain. Researchers from the Departments of Biology and Archaeology, University of Oxford, looked for worm eggs in the sediment samples taken from the pelvises of skeletons uncovered from ten archaeological sites investigated by Wessex Archaeology, such as Datchet, Larkhill and Bulford and the Southern Strategic Support Main.’

Aerial photograph of Larkhill, one of the sites from which environmental samples were taken. Image credit: Rob Rawcliffe of FIDES Flare Media Ltd.

About the University of Oxford’s research collaboration

- Researchers examined skeletons from before the Romans to the early Victorians for parasitic worm eggs

- Intestinal worms were a common problem for British people across a wide period of history

- The magnitude of the parasite problem in the UK changed over time

- Understanding how parasitic worm infections changed in the past can help public health measures in regions of the world still experiencing problems today.

Reshaping understanding of past populations

This type of research provides a unique insight into the lives and habits of past populations – their general health, cooking practices, diet, and hygiene.

Understanding how parasitic worm infections changed in the past can help public health measures in regions of the world still experiencing problems today.

Humans are infected with roundworms and whipworms through contamination by faecal matter and catch some tapeworms by eating raw or undercooked meat or fish.

Infections with parasitic worms are a big problem in many parts of the world today, particularly in some tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. But in the past, they were much more widespread and were common throughout Europe.

Investigating human burials

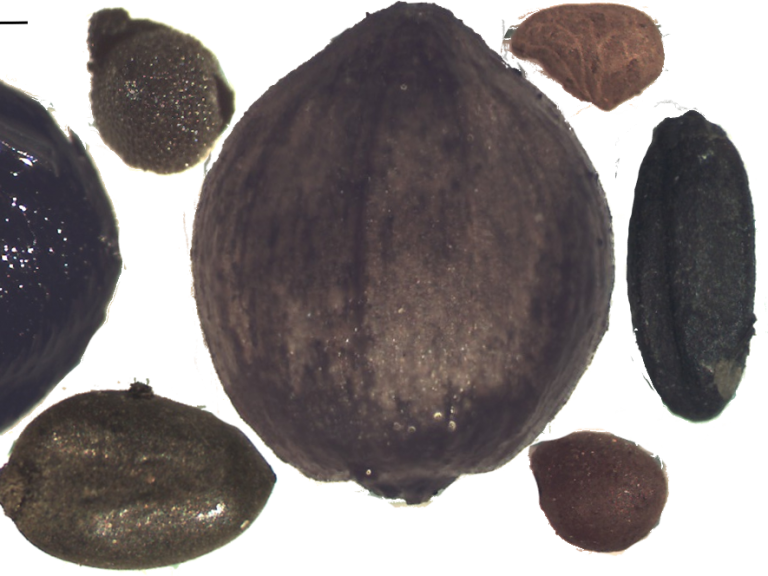

The research team wanted to find out the size and scale of parasitic worm infections in the UK over the course of history. So they looked for worm eggs in the soil from the pelvises of skeletons.

They tested a lot of individual skeletons. 464 human burials were examined from 17 sites, dating from the Bronze Age to the Industrial Revolution.

People In the Roman and the Late Medieval period fared the worst, with the highest rates of worm infection detected. The infection rates were similar to those seen in the most affected regions today.

Things changed in the Industrial period. Worm infection rates differed a lot between different sites – some sites had little evidence of infection, while in others there was a lot of infection.

The researchers think that local changes in sanitation and hygiene may have reduced infection in some areas before nationwide changes during the Victorian 'Sanitary Revolution'.

Environmental Archaeology team processing samples from site. Image credit: Wessex Archaeology

The co-first authors, Hannah Ryan and Patrik Flammer, said:

'Defining the patterns of infection with intestinal worms can help us to understand the health, diet, and habits of past populations. More than that, defining the factors that led to changes in infection levels (without modern drugs) can provide support for approaches to control these infections in modern populations.'

Research aims

The team will next use their array of parasite-based approaches to investigate other infections in the past. This includes more large-scale analyses of human burials, as well as continuing their ancient DNA work.

Their ambition is to employ a multidisciplinary approach, working closely with archaeologists, historians, parasitologists, biologists and other interested groups to use parasites to help understand the past.

Thank you to everyone involved

Principle Authors: Department of Zoology, University of Oxford

Project Partners: The research collaborators working with the University of Oxford team -

Oxford Archaeology Ltd, York Archaeological Trust, Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd, Worcester Cathedral, Wessex Archaeology, Institute of Archaeology, University College London, Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), University College Dublin (UCD)

Find out more about the research paper on the PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases research journal pages