First public vote

Between the 28th August and the 4th September 2020, the first of our public object votes was held. This meant that members of the public had the opportunity to be a part of the Lost & Found project and they got to vote on their favourite two objects from a selection of four.

You can watch the film below:

83 members of the public cast a vote. Here’s what some of our voters had to say.

“Awesome. The great thing about the Larkhill chalk block is that it could have been so easily overlooked. It was found in a World War I training trench that had been backfilled with chalk rubble. There were over 8km of trenches So finding a chalk block in amongst what would have been 100s if not 1000s of tons of chalk rubble is incredible…”

“Lol I love that you set the premier to encapsulate north American as well as European audiences. For me this airs at eleven so I'll have a wonderful lunch. Thanks for all you do. Your heritage and the human story as a whole are deeply united. Long live Wessex archaeology.”

“Very nicely done! Interesting stories and nice camera work. Thanks Phil and Erica!”

Examine the two selected objects below.

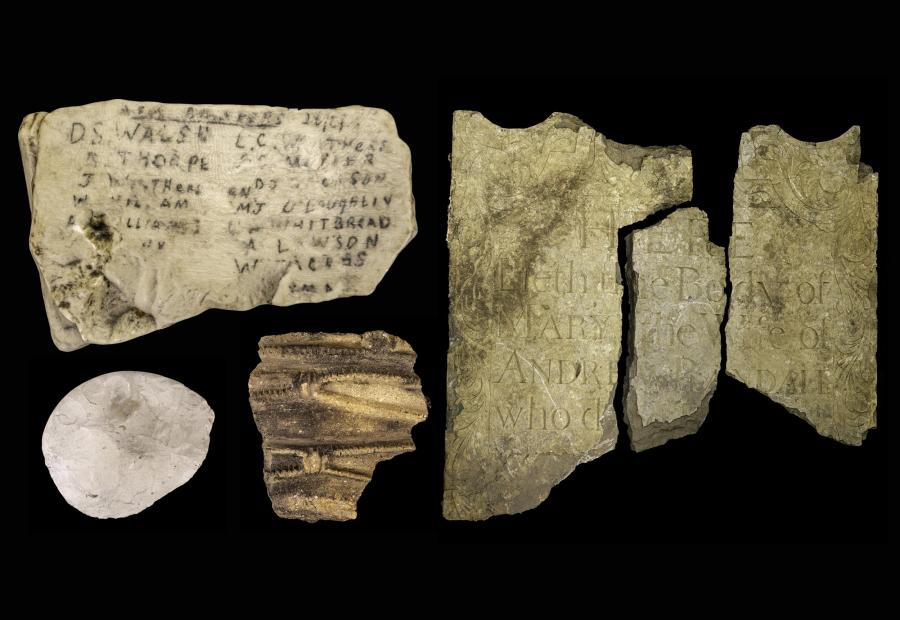

First World War chalk block

An irregular chalk block recovered from the deliberate backfill deposit of a communication trench at Larkhill. Under the heading ACOY BOMBERS 26/8/16 are the names of twelve Australian soldiers of A Company, 43rd Battalion, 11th Brigade, 3rd Division. Among the names is that of Lawrence Carthage Weathers, who would go on to be awarded the Victoria Cross – the highest medal for gallantry - for his actions in single-handedly storming German lines and capturing 180 prisoners and three machine guns at the battle of Mont St. Quintin on 2nd September 1918. Sadly Lawrence Weathers never learned of his award, as he was killed in action just a few weeks afterwards when a shell burst over where he was sheltering during the battle of St. Quentin Canal, and he died from the wounds he received.

18th century gravestone

Fragments from the gravestone of Mary Randall, recovered from a site at Endless Street in Salisbury. The gravestone is made from limestone, and the incised inscription and the shape of the slabs conform to the style of the middle of the 18th century. The wording on the gravestone reads “here lieth the body of Mary the wife of Andrew Randall who d—d D?.............th. Unfortunately the key date information is missing. A search of the parish records could not find any reference to Andrew Randall marrying a Mary, or a death in the correct date range. A search under the alternative spellings of Randell and Randoll produced more promising results, and showed that Andrew Randell/Randoll married Mary Burr on 28th October 1727. Both Andrew and Mary were from St. Edmund’s parish in Salisbury.

Second public vote

Our second public vote took place between 28th October – 4 November. We made the choice even harder this time, with Phil showing us four objects that he is particularly fond of. Take a look at the film below to see which two objects you would have chosen.

Just under 150 people voted and there were two clear winners, the discoidal flint knife (one of Phil’s favourites) and the pottery fragment (another of Phil’s favourites!)

Here’s what some of the public had to say:

"We love what you're like with a piece of flint, Phil! 💗 Thank you, Phil and Wessex Archaeology, for showing us these beautiful finds, teaching us about them, and keeping that fire of excitement in discovery and imagination burning. It's always a thrill"

"Thank you for presenting such interesting objects, and telling about how they were made. Love how Phil finds a link with the ancestors in each piece. Having worked at sites in Israel and Jordan, I can affirm his feelings, it makes you feel a physical and spiritual relationship with the makers of those objects. These pieces make you aware of the people who used them."

Late Neolithic Woodlands pottery

Pots are used to provide reliable indicators of date, they also reflect the character of the potter. Each coil or slab was added and carefully drawn up into shape, the fingertips lovingly smearing the clay to thin the pot walls. The potter then mimicked cord, each strand drawn together using stylised knots. The pot was then fired; a skill in itself.

This pot fragment from Bulford, is a fine example of the Late Neolithic style of potting known as the ‘Woodlands’ sub style, named after a bungalow on the outskirts of Amesbury, Wiltshire where the style was first recognised. It was made when construction work began at Stonehenge and may have been used by someone who visited the early site, nearly 5,000 years ago. The Bulford assemblage forms part of the largest group of ‘Woodlands’ pottery from southern Britain, yet the origins of the style are found on Orkney, where pottery of an identical style and decoration has been recognized, from where it spread to southern England.

Neolithic discoidal flint knife

This beautiful discoidal flint knife was found in a Late Neolithic pit at Bulford, Wilts. It is one of only 3-400 such objects from Britain and one of the few with an associated radio-carbon date, 2,950BC. The knife is a superb example of the flint knapper’s skill, using a thin flake, produced from a carefully prepared flint core and requiring a minimum amount of retouch, pure economy of effort, to create a perfectly circular object. The edge was then ground to produce a strong, relatively sharp edge. We do not know precisely how the knife might have been used, whether it was hafted or functioned as a scraper. Knives were essential objects, normally served by flint flakes; our ancestors must have appreciated the skill needed to make this special knife, valuing it highly; so why throw it away? It was found standing upright, suggesting that it may have been placed deliberately in a symbolic act of the type that we see elsewhere in prehistory, yet sadly struggle to explain satisfactorily.

Return to the Lost and Found Museum home page