Archaeological excavations at Longforth Farm, Wellington have revealed a Bronze Age landscape and a previously unknown complex of medieval buildings. The site has been excavated, ahead of development, by Wessex Archaeology, one of the largest archaeological practices in the UK. We work with councils, developers, landowners and heritage organisations to ensure that archaeological evidence is recorded and disseminated before work begins on new development schemes.

The excavations, funded by Bloor Homes and supported by Somerset County Council, have enabled us to examine and record this exciting archaeology and understand Wellington's hidden heritage. As a responsible developer, Bloor Homes have embraced the requirement for ecological and archaeological mitigation whilst addressing the housing needs of a continually expanding community.

The results of the excavations have been published in our Occasional Paper series.

A selection of the finds from Longforth Farm are on display at Wellington Museum.

Please check the Museum’s website for opening hours.

Community engagement

Wessex Archaeology was commissioned by Bloor Homes to undertake a community outreach project at Longforth Farm, Wellington in relation to a programme of archaeological mitigation. The objective was to promote community interest in the medieval building complex uncovered at Longforth Farm and to add value to the Bloor Homes development by fostering a sense of place and community though shared heritage assets.

Implementation

Wessex Archaeology, supported by Somerset County Council, delivered an extensive and inclusive week-long programme of activities that aimed to engage all age groups within the local community.

The media day at Longforth Farm was well attended by members of the television, radio and printed press. The interest generated by this event and the associated press release resulted in extensive media coverage on a local, national and international scale.

On-site school workshops took place over three days and over 250 children from four local schools participated. Workshops featured a tour of the archaeological site and the opportunity to design medieval floor tiles using clay. Feedback from all four schools was very positive and several of the students and teachers returned on the community open day.

The local historical society tours, which were fully booked, provided an in-depth opportunity for this specialist audience to preview the archaeology and the artefacts ahead of the community open day. They also provided an opportunity for society members to share their knowledge of the site and the area with us.

The community open day offered local residents an opportunity to explore this exciting archaeological site and discover a previously unknown part of Wellington’s heritage. Over 1400 people attended this free event; an unprecedented number that reflected the high levels of local interest in the site and the success of our media strategy. Activities included guided tours of the excavation area led by the archaeologists, and several hands-on children’s activities. Phil Harding, from Channel 4’s Time Team, was also on hand to meet visitors. Feedback from this event was overwhelmingly positive and there was great interest in future events, lectures and museum displays.

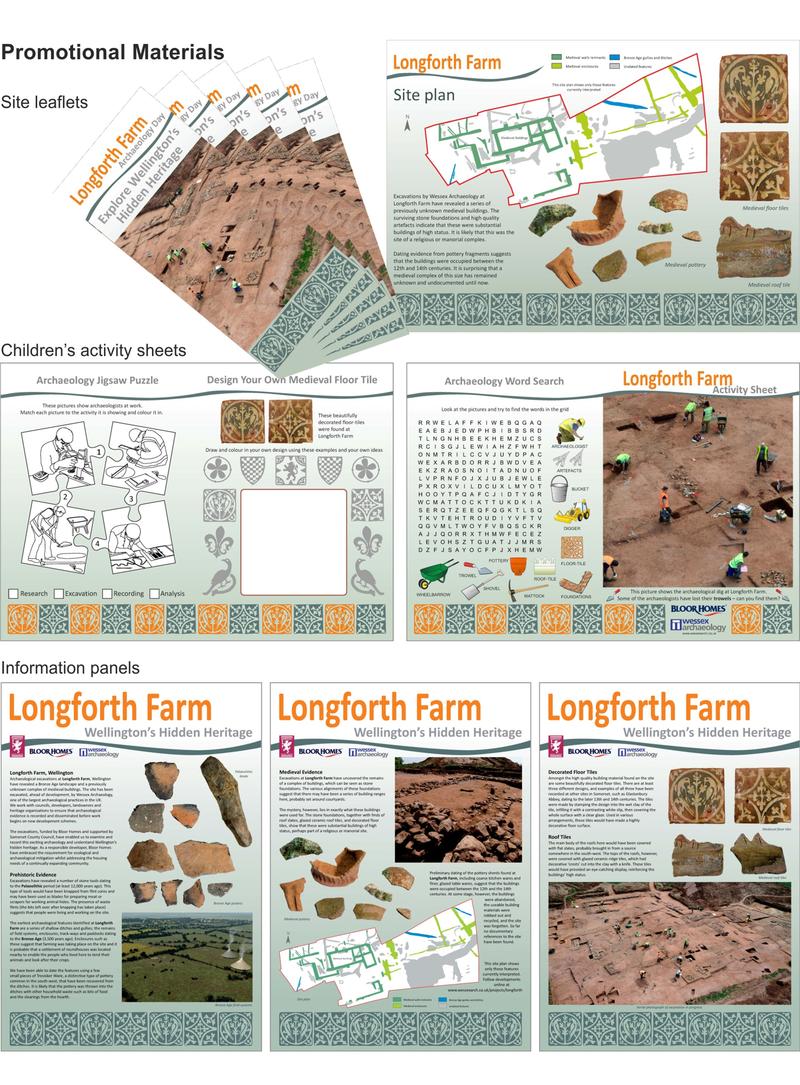

High quality promotional materials were produced by Wessex Archaeology’s specialist graphics team in support of the project, during the three-week preparation period. These materials included information panels, leaflets, activity sheets and a promotional flyer. In addition a set of project web pages was created on the Wessex Archaeology website and a successful social media strategy was implemented across several platforms.

Outcomes

The Longforth Farm community engagement project was a great success and an excellent example of partnership working. Wessex Archaeology’s effective health and safety management and event-specific risk assessments ensured smooth running of the project at all stages.

Local schools, societies and residents came together and were inspired by the archaeological site.

Over 1750 people engaged with the site throughout the week-long programme of events, and several thousands more accessed the information via the associated press coverage and online through our digital media. Feedback from all events was overwhelmingly positive.

Associated Links

Early Prehistory

The earliest evidence for human activity on the site − and indeed the region − is a Terminal Upper Palaeolithic blade dating to around 9500−8500 BC. This stone tool, made from Greensand chert, would have belonged to a hunter-gatherer passing through the area after the last Ice Age. It could have been used for chopping or cutting meat.

A concentration of Mesolithic (8500−4000 BC) flint blades was found around a former stream channel, perhaps the focus of a later temporary camp site.

Bronze Age

The earliest archaeological features identified at Longforth Farm are a series of shallow ditches and gullies; the remains of field systems, enclosures, trackways and paddocks dating to the Bronze Age (3500 years ago). Enclosures such as these suggest that farming was taking place on the site and it is probable that a settlement was located nearby. Although no buildings were identified in the excavation, activity was focused around a stream channel which would have provided a source of water. A dump of burnt stone may have come from a cooking hearth.

We have been able to date the features using a few small pieces of Trevisker Ware, a distinctive type of pottery common in the south-west, that have been recovered from the ditches. It is likely that the pottery was thrown into the ditches with other household waste such as bits of food and the clearings from the hearth.

Medieval buildings

The principal discovery at Longforth Farm was the remains of a previously unknown high status medieval building complex. The discovery of a substantial and extensive complex of medieval buildings was completely unexpected and raised a number of questions – what were the buildings, when were they built, who were they built for, and when and why did they disappear?

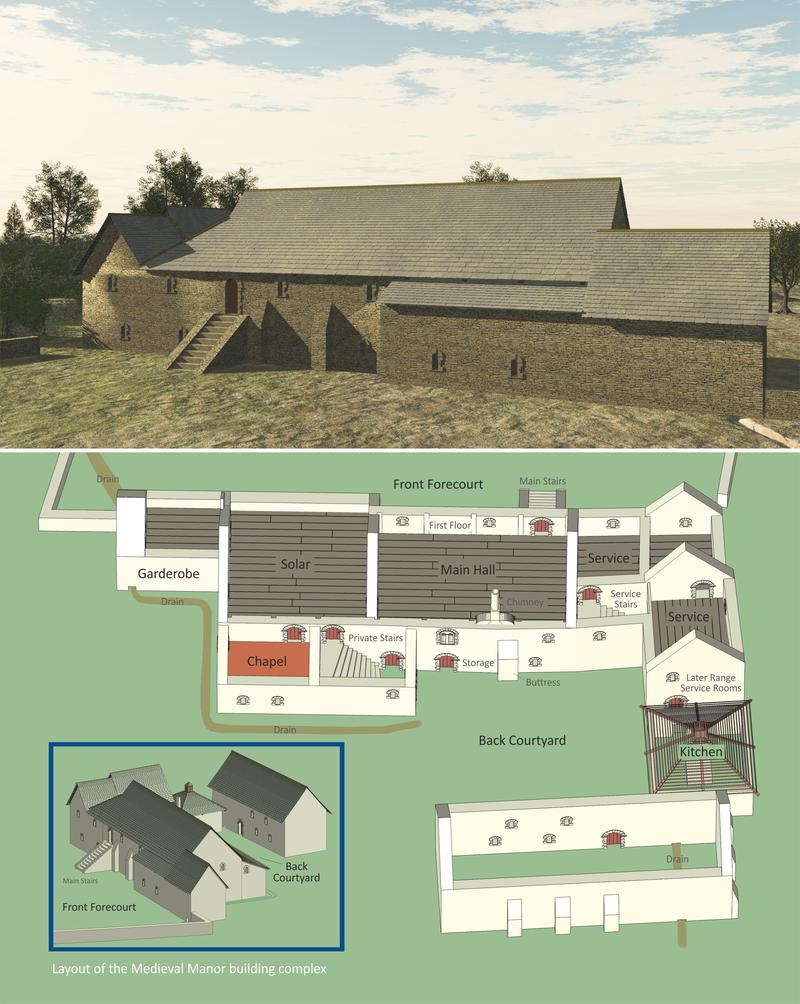

The building complex is thought to have been a manor house and though heavily robbed, key elements identified include a hall, solar with garderobe, and service wing. A forecourt lay to the north and a courtyard with at least one ancillary building and a possible detached kitchen to the south. To the east was a complex of enclosures and pits and beyond this a fishpond.

There was a restricted range and number of medieval finds, but together these suggest that occupation spanned the late 12th/early 13th century to the late 14th/early 15th century. There was a notable group of medieval floor tiles and roof furniture, but documentary research has failed to identify the owners and any records relating specifically to this important building. One possibility is that it belonged to the Bishops of Bath and Wells, and was perhaps abandoned around the end of the 14th century when they may have moved their court to within the nearby and then relatively new market town of Wellington.

In conclusion, we still don’t know for certain who built the manor house and why it was abandoned, but it represents a remarkable and unexpected discovery. Perhaps one day in the future a researcher will find documents lying undiscovered in a church archive or library that will provide answers to this medieval mystery.

Medieval pottery

Only a relatively small assemblage of medieval pottery was recovered (745 sherds) including coarse kitchen wares and finer glazed tablewares. However, its significance lies in its provenance from a high status rural settlement – a rarity within the region. The relative absence of pottery and other domestic refuse suggests that rubbish was disposed of elsewhere, outside the area excavated. Amongst the pottery were fragments of jars and several jugs, at least one of which came from south-west France. There were also two costrels, unusual vessels for holding liquids which copied leather containers, and were suspended from the belt.

Medieval floor tiles

At the west end of the house, in the area of the solar or principal chamber – and perhaps from the private chapel – was a group of glazed floor tile fragments, all manufactured around 1250−1300. There are seven designs amongst the decorated fragments, including heraldic examples of the St Barbe family and another showing Richard I and Saladin.

The tiles were made by stamping the design into wet clay infilled with a contrasting white slip, then covering the whole surface with a clear glaze. Used in various arrangements, these tiles would have made a highly decorative floor surface.

All of the designs recovered can be seen at Glastonbury Abbey, as well as Wells Cathedral, Cleeve Abbey and Bridgewater Friary. Tiled floors would have been expensive, and were most commonly found in buildings with an ecclesiastical connection, supporting the suggested link of the manor house with the Bishops of Bath and Wells.

Medieval roof tiles

A large number of broken roof slates were found during the excavation, left behind because they could not be reused. These stone slates came from the Brendon Hills, possibly from quarries at North Wiveliscombe or Treborough.

There were also many fragments of ceramic ridge tiles with crested tops and knife-slashed decoration, finished in a variety of green and yellow glazes. This detail is another indicator that the house was both impressive and of high status. The ridge tiles would have been used on the crest of the roof and would have been visible from the ground.