Springhead – an archaeologist’s dream

Update January 2012: The four-volume publication "Settling the Ebbsfleet Valley" is now available to buy.

Springhead in Kent was Wessex Archaeology’s longest-running and most prolific excavation. Around 30 archaeologists spent more than two years working at the site, finding more than 150,000 objects, ranging from axe heads dating to 300,000BC to a small hoard of Medieval silver pennies. The site was described as ‘an archaeologist’s dream’.

Wessex Archaeology had the chance to carry out this work in 2000-2003 because Springhead was on the route of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link and all important archaeological remains had to be excavated before construction work began.

Although the team found evidence of human activity going back to the Stone Age, it was during Iron Age and Roman times, from around 100BC to AD300, that Springhead was of particular significance as a religious centre with a nationally important complex of temples.

These pages tell the story of our work at Springhead.

The background

In 1998 work began on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, a 109km (68-mile) high-speed railway line between St Pancras and the Channel Tunnel. Part of the route of the link took it through Springhead in north Kent.

‘a once in a lifetime opportunity’

Under planning regulations all sites where construction takes place are assessed to see if any archaeological remains lie buried underground. This ensures that the impact of construction is understood.

At Springhead there was never any doubt that archaeological excavation would be needed, because the route of the railway line there took it through a centre of great religious importance in Roman Britain.

And it was not only in Roman times that Springhead was important. People have always been drawn to the area because of its natural advantages: as well as the springs, the site is a sheltered valley with good agricultural land and people could sail into the Thames from the River Ebbsfleet nearby.

For example: parts of the skull of an early form of human, dating back to the earliest part of the Stone Age, c400,000BC, had been found nearby at Swanscombe, and handaxes and flints from the Late Upper Palaeolithic (12,000BC-10,000BC) and the Mesolithic (8,500BC-4,000BC) were unearthed during Wessex’s excavations at Springhead.

But it was in Iron Age and Roman times, from around 100BC-AD300, that Springhead produces its most important archaeological remains, as the rest of these pages demonstrate.

Rail Link Engineering, the consortium responsible for the design and project management of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, which was funded by Union Railways (North) Limited, took up the challenge of ensuring that all the important archaeological remains were excavated from the site, and employed Wessex Archaeology to carry out the work, in liaison with its own archaeologists.

For Wessex Archaeology, Springhead began as a five-month project to excavate in September 2000, but work continued until spring 2003 as Wessex was awarded more contracts in what turned out to be an immensely rich archaeological area.

Phil Andrews, the project officer in day-to-day charge of the site, who has 25 years’ experience in archaeology, has no doubt about its importance.

“The excavation was one of the richest in the country in terms of archaeology,” he said. “It was a huge site, multi-period and stratified, and so well preserved. It is a very famous spot and we were lucky to have had the chance to excavate there on the scale we did – it was a once in a lifetime opportunity. I don’t expect I’ll get a chance to work on a site like that again.”

The excavation

Springhead was an archaeologist’s dream: every day something new was found – coins, brooches, pottery, sometimes weapons or skeletons. Numbers alone tell a story: at least 60,000 tonnes of earth shifted; 150,000 artefacts discovered; finds ranging from 300,000 BC to AD1500; an excavation lasting more than two years; up to 30 staff digging at one time. This was Wessex Archaeology’s longest-running, most prolific and wide-ranging project.

It was a noisy dream, to be sure, as the site was next to the unstoppable juggernaut of A2 traffic between London and Canterbury. But the conditions could not dim the enthusiasm of the diggers who worked at the excavation.

Springhead was also notable for the unusual depth of the soil, four metres in places, on the site. Though this meant extra work when excavating, it also helped to preserve many of the finds from damage by ploughing.

The team were well supported: as well as Wessex’s own experts, external specialists from a number of different areas were involved, including soil scientists, pollen specialists, experts on the Roman period and prehistorians.

Rail Link Engineering (the consortium responsible for the design and project management of the rail link) had a full-time team of five archaeologists, all of whom were closely involved in the work. Regular monitoring meetings were held attended by representatives of English Heritage and Kent County Council as well as Wessex Archaeology and RLE.

The temple complex

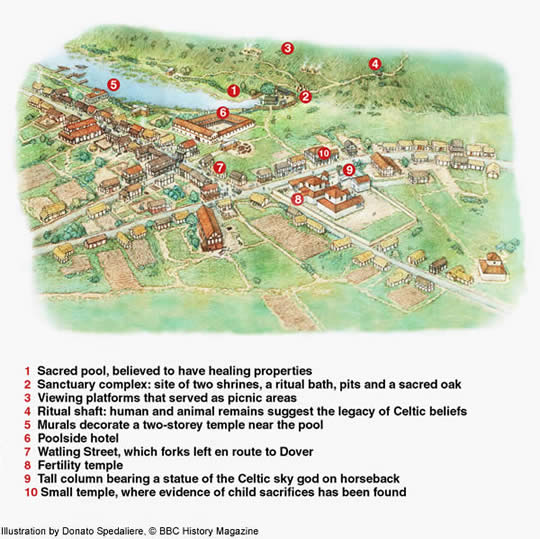

At the heart of Springhead, at the head of the River Ebbsfleet, was a pool fed by eight natural springs, an unusually large number that made the site sacred to the Celts, who began settling there around 100BC. They called the site Vagniacis (‘the place of marshes’). Excavation revealed a 600-metre ceremonial way, sacred pits filled with animal remains and pots, as well as numerous coins.

The Romans were also drawn to the site’s religious significance after they invaded in AD43, though their first aim was to make sure their occupation was secure – they built what seems to have been a supply base at Springhead, reached by a road from the River Ebbsfleet. But the fact that the base was used only briefly, and no fort was built, suggests that Kent did not resist the invasion strongly.

It was not a military connection that made Vagniacis so important, but religion and trade. The Romans connected the area to the rest of the country when they put one of their famously straight roads, Watling Street, from Dover to London, right through Vagniacis (its route was directly underneath Wessex Archaeology’s site office).

This would have brought to Vagniacis both travellers wanting to rest on their journey between the capital and the coast, as well as pilgrims attracted to the springs. We see this in the archaeological evidence for a succession of buildings put up on the side of the road, culminating in a stunning complex of perhaps as many as a dozen temples established in the late 1st century AD.

By the end of the first century AD Vagniacis had a population of perhaps 1,000-2,000 and its central area was about 15 hectares in area (37 acres). Around the sacred pool was a walled sanctuary containing one, possibly two, shrines or temples, a large tree, a tank or bath, a small booth for baking bread, and several sacrificial pits where dead animals and pottery were placed. Overlooking the pool were platforms which may have been put up to allow visitors to view the sacred pool. Near the southern end of the pool was a structure which may have been a guest house where pilgrims were housed.

Strewn on the floors of some of Vagniacis’s temples were votive offerings and religious paraphernalia, including a ceramic figurine of a goddess and a stone altar.

In one temple the bodies of four children were buried: two were headless, probably decapitated after death as part of a religious ritual. In a bakery nearby were 14 other child burials. Whether these were human sacrifices or had simply died from natural causes, we cannot tell. Not far from the pool was a deep shaft filled with ritual deposits inlcuding one human and various animal skulls, perhaps buried there as part of a ritual.

If these were indeed human sacrifices then it tells us that the Celtic influence on Vagniacis was still important, because the Romans disapproved of this practice.

Ten of the Springhead temples were unearthed during earlier excavations from the 1950s to 1980s, but two, including a sanctuary complex, were found by Wessex’s staff. This may be the oldest of the religious structures in Vagniacis.

The complex comprised a central cella or shrine, with a pair of stone columns on the front, set within a temenos (sacred enclosure) which included a portico structure which may have been another shrine or temple. It is not certain to whom the principal shrine or temple was dedicated, but in the now-dry riverbed were found a large number of Roman coins and brooches.

Across the pool from the sanctuary complex was another temple excavated by Wessex Archaeology. This was built of stone, had a central tower and tiled floors, and traces of wall painting survived.

“The town is unique in Britain for its extraordinary complex of temples and shrines and the remarkable finds that have come from them,“ said Phil Andrews, the project officer for Wessex Archaeology at Springhead.

The Roman settlement was not simply religious in nature. This was a place that also provided for the needs of travellers using Watling Street between London and Rochester, Canterbury and Dover as well as those sailing small vessels to and from the Thames via the Ebbsfleet.

Along Watling Street Wessex staff found various buildings including an aisled barn, two smithies, a bakery, a possible dyeing complex, a bathhouse, and at least one roadside shrine at a street junction. The final stage of excavation exposed the 2-4th century AD town waterfront on the west side of the Ebbsfleet.

The temples may have fallen into disuse in the 4th century when the advent of Christianity led to the emperors suppressing pagan sites. But the site’s archaeological importance did not end with the Romans – nearby was found a richly furnished Saxon cemetery dating to AD650-700, with skeletons, buried with jewellery, coins and weapons. This was probably used by villagers from a settlement a few hundred metres away in the valley bottom.

A few dozen pieces of medieval pottery, several silver pennies and a pilgrim’s lead container for holy water testify to activity in the Middle Ages, when the area was still a place where travellers could find shelter and provisions. But in later centuries the road to London diverted farther north and the area fell into disuse. Its fortunes did not revive until the Ebbsfleet was used for the cultivation of watercress in the 19th century, the earliest commercial production in the country.

Metal detecting

Springhead saw the coming of age of a device traditionally viewed as the enemy of archaeologists: the metal detector.

Detectorists with more enthusiasm than knowledge have been blamed by archaeologists for removing finds without documenting their context; on occasions they have been accused of outright theft from sites. (Fortunately the Portable Antiquities Scheme is doing much to promote the voluntary recording of such finds).

Any excavation runs the risk of an unofficial visit from detectorists. Archaeologists have used their own metal detectors mainly as a defensive tool to combat this by getting everything detectable out of the ground before anyone else can.

But the responsible use of metal detectors can reveal finds that could otherwise be missed, as Springhead showed most clearly. In the original contract between Wessex and Rail Link Engineering, there was a clause requiring a metal detecting survey of the site.

Wessex Archaeology decided the expertise of a local detectorist group would be the best way forward and contacted the 30-strong Dartford Area Relic and Recovery Club. They wanted one member to be on hand regularly so that a good relationship could be built on both sides.

Step forward Roger Richards, who took up the hobby of detecting full-time after selling his successful sheet metal business. Roger worked unpaid as a volunteer almost every day on the site. He first thought he would work for the five months the first contract was expected to run, but ended up staying for the whole two years.

"It went from one thing to another once I realised I could get on with everybody here," said Roger. "They made me feel part of the team and that’s one reason I stayed".

The effect of Roger’s staying was enormous. About three-quarters of the metal objects at the site were found by him using his detector. These included two thousand Roman coins, 80 Celtic coins, a hundred brooches and a large and well preserved Saxon sword. It was his discovery of a brooch on the slope that revealed the Saxon cemetery.

"I never realised it was going to go on so long" said Roger. "I did it to prove a point about how well metal detecting can work with the right sort of people. Archaeologists are now recognising how effective it can be. Some of the older ones may be set in their ways but the younger ones are seeing the benefits of using them".

Phil Andrews agrees. "It’s been invaluable" he said. "So many of the finds would not have come to light without Roger’s work. I think that this scale of detecting should go on at the majority of sites that we run".

The inside story

An archaeologist’s point of view

“it felt like you were treading in archaeology”

One of the longest-serving members of staff was Becky Fitzpatrick, who began work as a project assistant at Springhead in 2001 after completing a degree and post-graduate course in Marine Archaeology at Southampton University.

"It was great to watch a site reveal itself in all its different periods of occupation and see the whole process from beginning to end, from evaluation to packing up tools at the end of the dig" she said.

"It was fascinating to find individual lovely pieces of archaeology such as brooches. We were so spoiled on this site for finds - sometimes it felt like there were so many that you were treading in archaeology".

She has found spatulas, coins, pin bones and pottery but her most exciting moment was finding a huge Saxon sword on the site of the cemetery with the help of Roger Richards.

Post-excavation

A Visigoth in Kent?

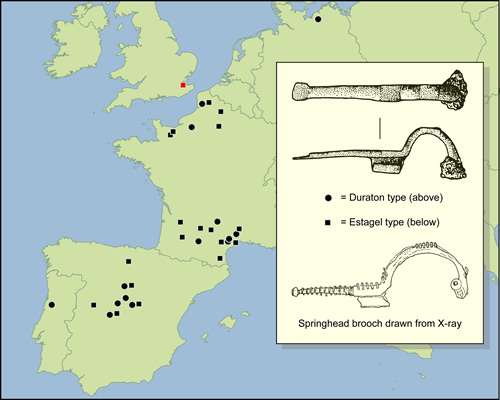

The excavations at Springhead uncovered a large number of brooches. One in particular has turned out to be a very exciting discovery. X-ray photography showed that the 5th-6th century iron bow brooch was of Visigothic design, of a type known as Estagel. The Visigoths (West Goths) were one of the Germanic tribes. Settled near the Black Sea in the 3rd century AD, by the 6th century they had migrated west and reached Spain and northern France.

Kent was probably the most cosmopolitan region in the country at this time and Saxons and Jutes have left evidence of their culture here. In the last 30 years or so, a number of objects of Visigothic design have come to light, mainly in south-east England. Now this brooch adds to the evidence for connections between the people of Kent and the small number of Visigothic groups known to have lived in northern France at the time.

To discover more about this brooch and its significance, download the full article below, as published in LUCERNA - The Roman Finds Group Newsletter for January 2006.

|

|

|