Investigations at Kingsmead Quarry, Horton, Berkshire, have revealed a complex archaeological landscape and evidence that people had used the area since the end of the last Ice Age, a period of over 12,000 years.

Rivers have always been important for settlement, as a source of water and as a means of transport and communication. This site lies on a floodplain and the River Thames, which would have had more channels than today, may once have crossed the southern part of the site. This would help explain why people have used and occupied this area for so many years.

Large areas of the site have been excavated, allowing us to view entire landscapes. This has enabled us to understand how the area was utilised throughout history. The method has also revealed some amazing discoveries which may otherwise have been lost or not seen. Some of the finds recovered from the excavations are of national importance, including the remains of four Early Neolithic (3750 BC) houses and a rare Beaker burial (2300 BC).

The quarry is owned and run by CEMEX UK, who extract sand and gravel from the site. Archaeological layers lie beneath the modern ground surface but above the natural gravel, and so needs to be investigated before any extraction can take place. A lot of the work was also associated with the construction of a new state of the art gravel processing plant which was installed in 2008. Unexcavated areas of the site remain as arable fields.

An excavation team from Wessex Archaeology has been investigating the site since 2003, with further excavation planned for the next two years. To date, over 28 hectares of the quarry have been examined.

Associated links

Environment and palaeochannels

The archaeological evidence that we see on the site has been dug into the natural geology for several millennia. The site is located in an area of floodplain gravels within the Middle Thames Valley. Natural clay called ‘brickearth’ overlies several metres of gravel terraces that were laid down up to 300,000 year ago (Devensian period). It is these gravels that require extraction and the need for quarries in the west of London around Heathrow.

The excavations of a series of old river channels within and to the edges of the archaeological excavations have also provided information on the nature of the site. The channel systems show that a large watercourse, possibly an ancient course of the Thames, ran across the southern edge of the site. Other evidence indicates channel activity during the Neolithic and Bronze Age landscapes. The data recovered has enabled a relatively detailed chronological framework for the development and evolution of the palaeochannels.

Each of the channels has been studied by geoarchaeologists who can gauge their development, chronology and impact on the settlements and farming communities that lived on the site.

Pre-Neolithic

Amongst the objects recovered were a number of flints dating to the end of the last Ice Age (10,000 BC).

A far older object, a Palaeolithic (old stone age) cordate flint hand axe, around 300,000 years old, was found by a quarry worker in the extracted gravel. The true location of the hand axe is not known, although it is known to be far older than the gravel terrace deposit that it probably derived from.

Excavations also revealed an assemblage of flints dating to the end of the last Ice Age, a period which archaeologists call the Late Upper Palaeolithic (12,000-10,000 BC). At this time Britain was still joined to mainland Europe.

Many of the flints, from ‘long’ or ‘bruised-blade’ industries, were located within the vicinity of an old river channel, whilst others were recovered from a layer of old soil that had survived in a slight hollow. The long blades would have been used as knives and may have been brought to the site by people hunting and gathering along the rivers Colne and Thames.

A number of flints were recovered from hollows left by fallen trees, whilst a significant flint scatter comprising a number of blades, cores and burins (for working antler and bone) was found, believed to be of Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic date (12,000-4000 BC). The distribution of the flints suggests an area of tool manufacture.

Neolithic Houses

The excavations have revealed some of the most significant evidence for occupation during the early Neolithic period (4000-3300 BC) in England. The findings have made Horton one of the most important Neolithic sites currently under investigation in the country.

By this time Britain was an island and people had started to grow crops and keep animals. Evidence for settlement from this period is ordinarily very rare. However, a total of four Neolithic structures have been found on the site to date, representing some of England’s oldest houses. In southern England, to find one house would be exceptional but to find multiple examples makes this an important site. Of course not all of our structures are necessarily of the same date; they could represent the houses or feasting halls of a small community that shifted location over one or more generations, perhaps as decay set in. Further analysis and radiocarbon dates will aid their understanding and chronology.

The structures represent two different styles of construction, but all were rectangular. Two of the buildings were post-built, relatively small and with limited artefactual and dating evidence. The remaining two had foundation trenches, which appear to have supported upright wooden posts and planks. Postholes in each corner and two in the centre were associated with internal partitions dividing the interior into two rooms. These may have supported an upper storey in parts of the houses. We have very little idea of how the structures would have looked above ground. They may have had pitched roofs covered with thatch or turf.

Artefactual evidence from the buildings suggests they were used, at least for some of the time, as houses. Pottery of Early Neolithic date (3800-3350 BC), burnt flint, fragments of animal bone, flint working waste and a number of worked flint tools were recovered from the buildings. Charcoal and charred plant remains, including cereal grain and hazelnut shell were also found. Other finds include leaf-shaped arrowheads, rubbing stones, a polished bone point (or awl) fragment and a polished stone flake from an axe made in Cumbria.

Neolithic pits

A small cluster of Early Neolithic pits were located close to one the houses, and radiocarbon dates suggest that they were dug a few generations after the structure went out of use. The pits contained a high volume of finds, including arrowheads, pottery, worked flint, burnt flint, animal bone and fired clay. These finds indicate that the pits were used for domestic refuse. Further significance of the pits was suggested by two fragments of a highly polished worked bone point (or awl) that was broken into two and then deposited into separate pits.

A more dispersed scatter of pits represented Late Neolithic activity on the site, with some containing deliberately broken and placed artefacts, including Grooved Ware pottery sherds. Several pits contained many charred fruits and nuts, including whole sloes, wild crab apple and hazelnut shells. One important feature contained many items that were broken and deliberately placed, including pottery from four different vessels, a Peterborough Ware pottery sherd (already over 500 years old before deposition) and a burnt and broken discoidal polished knife fragment.

Neolithic oval barrow

A large Neolithic oval barrow was excavated on the site, having been previously partially investigated in 1990 by Thames Valley Archaeological Services (TVAS). The excavations focused on two concentric cropmarks that were visible from aerial photographs. The investigations revealed a ‘U’-shaped enclosure surrounded by a later oval barrow, built during a secondary phase of construction.

The Early Neolithic inner ditch contained midden-like material including large quantities of animal bone, possibly the result of feasting. The lower fills of the continuous outer ditch contained a series of placed deposits including a Fengate Ware bowl and a number of birch bark bowls. A number of antler picks were also placed at intervals around the base of the outer ditch and may have been used to initially excavate the monument. Other finds included several broken arrowheads, pottery and animal bone.

The oval barrow is one of only a few such monuments found in the Middle Thames Valley. These monuments were used in ceremonies, as places where votive offerings were made and, occasionally, for the selective burial of important individuals.

Beaker burial - A woman of importance

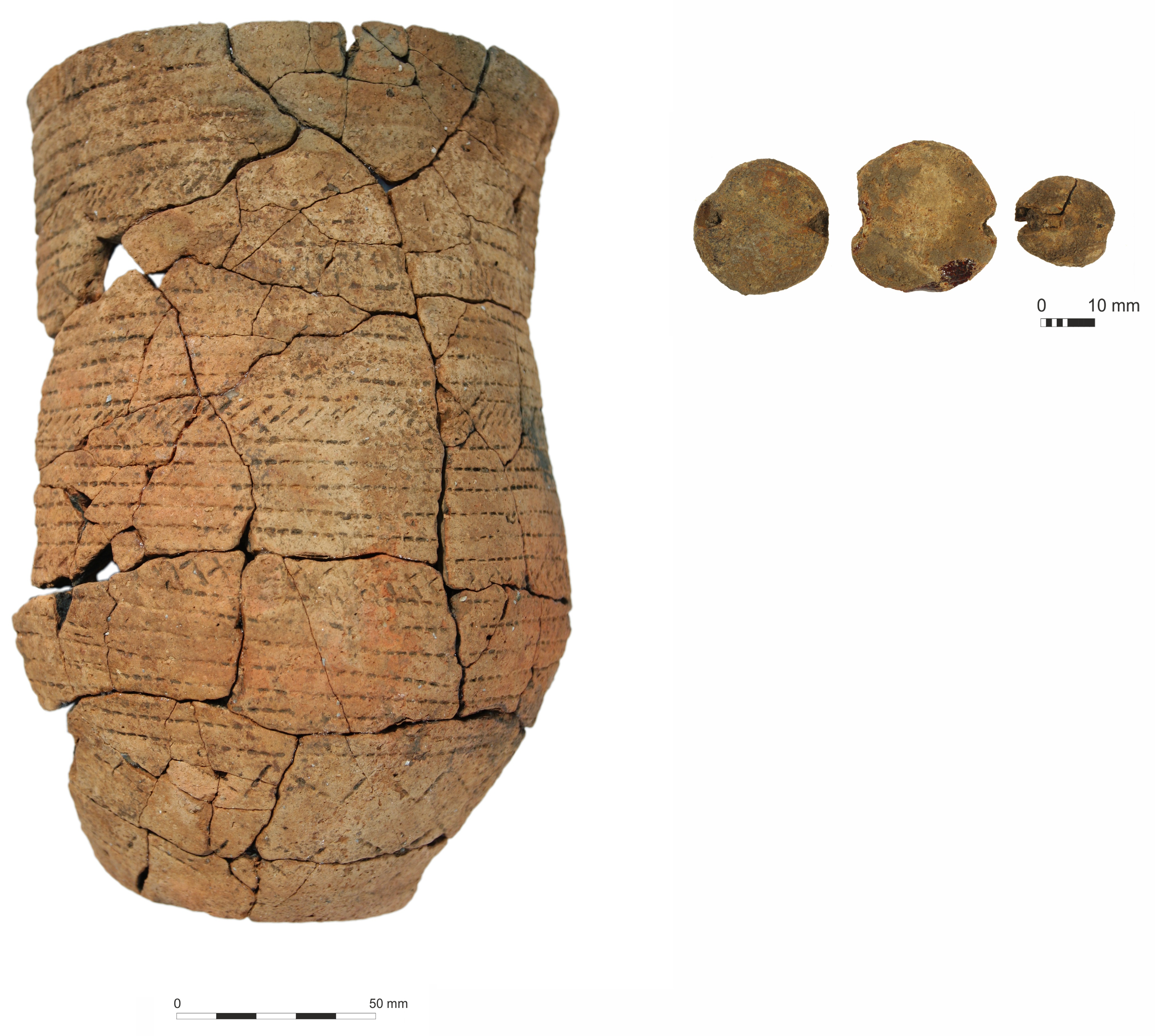

A rare Beaker burial, possibly of a woman aged over 35 years, was found in a small earth dug grave at Kingsmead Quarry. The burial contained a number of grave goods, including the remnants of at least one necklace represented by several gold foil beads, some large amber beads and many small black beads of lignite, a material similar to jet. A complete, although broken, fine and decorated pottery vessel or Beaker was positioned at the individual’s torso.

The grave represents a rare and unusual find. Such burials are extremely rare in south-east England, whilst such grave goods indicate a particularly important individual. Only a small number of Beaker graves in Britain, and indeed continental Europe, contain gold ornaments and as such they represent some of the earliest goldwork found in the country. Whoever the person was they were buried according to a rite that was new to Britain and more familiar to areas of Europe. The necklace of fine, rare and exotic objects, in particular beads of gold would have marked this person out as special, important and of high status within the community.

Associated links

Early Bronze Age

Little evidence for activity in the Early Bronze Age (2400-1600 BC) was recovered during the excavations at Kingsmead Quarry, but for a few significant features.

Two significant monuments were excavated on the site. A large continuous circular barrow and a large ring ditch, would have dominated an otherwise open and unenclosed landscape. Both ring ditches contained small quantities of Collared Urn and Beaker pottery, animal bone and worked flint. One monument was reused in the Romano-British period, when 55 shallow pits were dug immediately within the ring ditch. Residual Romano-British pottery was also recovered from the upper fills of the ditch. It is unclear why the shallow pits were cut immediately within the monument, and why it continued to hold such importance, although it is not unusual for prehistoric earthworks to be reused in later periods.

Both monuments were the focus of funerary and votive activity, with one being associated with a later Middle Bronze Age cemetery consisting of a large number of both urned and unurned cremation burials. Eight inhumation burials were also associated and appear to have been contemporary. A large circular post-built structure was also located nearby. In the more northern ring ditch deposits of animal bone including skulls were placed in the ditch.

An unusual feature of Early/Middle Bronze Age (1800-1500BC) was found within one of the farmsteads. A large pit of earlier date, perhaps Neolithic, was truncated by the insertion of an oven. Associated with this was a remarkable collection of flints and tools deposited directly onto the base of the oven. These included eight arrowheads of flint, a whetstone used for sharpening tools and an awl or punch made of bronze. This 'tool kit' may have been deliberately placed in the ground as a votive offering.

The distinctively shaped barbed and tanged arrowheads date to the Early Bronze Age, whilst the awl or punch is of Early/Middle Bronze Age. The arrowheads are thought to come from a number of different sources, and some of them can be grouped into pairs by their shape and size. Amber beads were also recovered from this pit along with evidence for bronze working. The combination of old and new material, objects that had be assembled and carefully arranged all suggest a ritual or votive deposit. One possibility is that this served as a foundation deposit for the creation of the farmstead – a symbolic burying of an old way of life.

Middle Bronze Age

Middle Bronze Age

At the start of the Middle Bronze Age (1500-1100 BC) people reorganised the once open landscape into a system of fields and farms at Kingsmead Quarry. So far the investigations have identified two separate farmsteads with associated paddocks and fields.

Both settlements had post-built roundhouses, fencelines, pits and waterholes. Several cattle burials were found associated with one of the farmsteads, and may indicate the importance of cattle to the communities’ economy at this time.

Finds from the period include two significant bronze finds, one from each of the settlements. A ‘quoit-headed’ pin was recovered from the upper fill of a boundary ditch, and possibly represents a ‘votive’ offering or a placed deposit. The quoit-headed pin would have been used to fasten a cloak or a piece of clothing and may have been buried deliberately. A decorative pin of ‘Picardy’ type was recovered from the corner of a segmented enclosure, apparently from a random and non-ritualised deposition. The pin shaft has a complex incised linear motif and, although now missing, the pin-head may have held a setting of glass or amber.

Pottery from the farm included a complete globular vessel recovered from the bottom of a waterhole. Vessels of this date are rarely found complete, and this one may have been carefully placed in the waterhole as a votive offering. It has a number of perforated lugs, perhaps to allow it to be suspended over a fire. Soot on the outside and charred food on the inside of the pot support this idea. This pottery type is a fineware made at a time when bigger, coarser vessels, called Bucket or Barrel Urns, were the more common style of pottery.

Iron Age

By the Late Bronze Age there was a change in the farming practices undertaken at Lingsmead Quarry, Horton. The farms and field systems used in the Middle Bronze Age went out of use and were abandoned. This may have been because the land had been over-farmed or because the area had become much wetter, forcing people to live further away in higher, drier locations.

Evidence for activity in the Iron Age (700 BC- AD 43) was limited to the north-eastern parts of the site, with examples of settlement and farming practices showing a distinct change to those seen during the Bronze Age. Settlement and farming practices appear to have moved towards a smaller and more contained riverside settlement characterised by roundhouses, post-built structures and enclosure ditches. Evidence for agricultural and domestic activities was recorded.

A large roundhouse of Early/Middle Iron Age date appeared to be the main focus of activity at this time. Two contemporary four-post structures were located nearby. Several areas of pit clusters suggest repeated and established activities in the area, possibly for the quarrying of clay for pottery making or for use as refuse pits. One zone of pit digging may have been an area of industrial activity, perhaps for loomweight production.

Areas of settlement were removed during the Late Iron Age, to be replaced by substantial agricultural enclosure ditches as part of a large-scale restructuring of the landscape. Domestic use of the land was relocated to an unknown area, as the sub-division of the area into workable plots of land for pasture and arable farming took effect. Many of these alignments and enclosures were reused or modified in the Romano-British period.

Romano-British

An area of activity during the Romano-British period (AD 43-410) was noted to the north of the Kingsmead site, and represents a large-scale farmstead dating from soon after the conquest to well into the late Roman period. Although no structures were recorded of this date, a large and complex farmstead formed of large enclosure ditches, pits and waterholes was developed, possibly to produce goods to be traded at nearby Pontibus (Staines-on-Thames).

Pottery recovered from the farmstead suggests an uninterrupted occupation throughout the period, and evidence has shown that the farm grew over time, as more and more enclosures were added. Such continuity suggests a period of prolonged and intensive period of agricultural activity.

The general intensification and nature of the landscape during this period was noted in the artefactual evidence recovered from the site. Pottery included decorated samian ware, suggesting a certain status to the Romano-British population at Horton, whilst specific artefacts have suggested a wider network of trade and exchange. These include a hippo sandal (a type of horseshoe), farm tools, and a small number of personal items, including brooches, a finger-ring and a copper alloy spoon/scoop from a toilet set. A rare bronze cauldron may have been used as a votive deposit, whilst four leather shoes were found from separate features within the farmstead.

There is very little evidence for Saxon activity from the site, although a single burial was found. The scarcity of evidence may suggest that occupation during this period was restricted to hamlets and villages, much of which may be beneath modern settlements.

Medieval and post-medieval

Evidence of medieval archaeology was sparse at Horton. Scatters of ditches and pits were noted to the north of the site, and these may have related to Horton Manor and Manor Farm. Recorded in Domesday Book in 1086, Horton Manor was held by Walter son of Other, and assessed at 10 hides, and remained a focal point throughout the medieval period.

A reasonably sized medieval field system was located at the southern end of the site, and may relate to agricultural activity close to the nearby village of Wraysbury. Such evidence suggests that pastoral enclosures or paddocks were located predominantly on the wetter, lower areas close to the course of the Colne Brook. Other evidence includes boundary ditches, pits and a small oven or kiln.

Evidence for post-medieval activity was limited, and some field boundaries and trackways coincide with historic mapping and indicate a large-scale sub-division of the landscape for agricultural purposes. Discrete features such as wells and animal burials suggest sporadic impressions on the landscape, and a large oval shaped enclosure may belong to a landscape feature associated with the later years of Horton Manor and Manor farm.

Community engagement

Wessex Archaeology along with our client CEMEX UK wanted the public to be able to learn more about this amazing site and gain community benefit from the work undertaken. We created a professional exhibition to be displayed in the local village hall in Wraysbury. A comprehensive programme of events was planned to engage with a range of audiences.

Implementation

A high quality exhibition was designed and produced by our in-house expert team to showcase what had been discovered. As well as 18 exhibition banners and a rolling video, two glass cases displayed a range of important artefacts from the site, some of which had been recently featured in the national news due to a series of press releases. This exhibition was previewed by the press and a range of dignitaries including local councillors, curators and planners, and was opened by the Mayor of Royal Windsor and Maidenhead.

Local schools were invited to take part in workshops to learn more about the site through talks and activities, such as making their own versions of the pottery recovered from the site. Activity sheets guiding them around the exhibition ensured that they learnt about the key aspects of the displays. An evening lecture by the archaeologists that led the excavations allowed a more in-depth presentation of the site and the discoveries.

The highlight of the two day event was the public open day, which attracted a range of people from both the local community and further afield. The demonstrations from Wessex Archaeology’s staff, including Time Team’s Phil Harding and Jackie McKinley, were extremely popular and attracted a wide audience to the event.

After the Event

In-school workshops by Wessex Archaeology’s Community & Education Officer took the story into the classrooms of a number of local schools, meaning that in total more than 370 schoolchildren learnt about the site.

The exhibition has since been installed at two of the client’s offices, and a future programme of public venues is planned.

Outcomes

These events generated significant attention with interviews on BBC Radio and articles in the local and national press, including The Independent and The Guardian. The story was also picked up in Spain, Germany and the USA. Over 500 people attended the open day and all of the feedback from the event was positive. Publicising the events through Wessex Archaeology’s website and social media meant that many thousands more people learnt about the site than were able to attend the open day. This generated significant coverage of the work, that has been funded by CEMEX UK, and the exceptional archaeology that was discovered.

Meet the archaeologists

Over 100 archaeologists and specialists have worked on the Kingsmead Quarry, Horton, project since Wessex Archaeology began their excavations in 2003. Below we reference and thank everyone who has contributed to this fantastic archaeological project.

Gareth Chaffey – Gareth was the principal site director. He is also the lead author of the forthcoming publication.

Alistair Barclay – Alistair is the project’s post-excavation manager since 2008 and also a lead author of the forthcoming publication.

Andrew Manning – Andrew is the project’s fieldwork manager and has been involved in the project since 2011.

Ruth Pelling – Ruth was the lead environmental specialist on the project and is one of the lead authors of the forthcoming publication.

Karen Nichols – Karen has been the project’s principal illustrator for many years, working on all forms of illustration, from publication figures and photographs to 3D reconstructions and animations.

Excavation team

Managers and Supervisors: Angela Batt, Elina Brook, Howard Brown, Caroline Budd, James Chapman, Rob De’Athe, Simon Flaherty, Rebecca Fitzpatrick, Matthew Kendall, Paul McCulloch, Piotr Orczewski, John Powell, Julia Sulikowska and Vasilis Tsamis.

Excavators: Dickon Agnew, Pascal Alliot, Andrew Armstrong, Owen Bachelor, Mark Bagwell, Andrew Baines, Steve Beach, Nick Best, Jeremy Bond, Cristina Bravo-Asensio, David Budd, Thomas Burt, Charlotte Burton, Damien Campbell-Bell, Laura Cassie, Laura Catlin, Keiron Cheek, Paul Clarke, Robert Cole, Charlotte Coles, Jo Condliffe, Paul Cooke, Rachel Cruse, Benjamin Cullen, Brenton Culshaw, Claire Davies, Stella De Villiers, Jonathon Diffey, Claudia Eicher, Vicki Gallagher, Richard Good, Samuel Fairhead, Dorothee Facquez, Matthew Fenn, Neil Fitzpatrick, Michael Fleming, Mikael Fredholm, Darrly Freer, Oliver Good, Jasmine Hall, Katherine Hamilton, Michael Hartwell, Jonathon Henckert, Karen Hole, Martin Huggon, Peter James, Daniel Joyce, Marie Kelleher, Steve Kemp, Ilona Kruk, Steve Leech, Emily Loughman, Marie Lundberg, Kenneth Lydon, Charlotte Martin, Jon Martin, Catrin Matthews, Andrew Mayfield, Lisa McCaig, Simon McCann, Martin McGonigle, Christopher Merrifield, Rachael Morgan, Alexander Moss, Jeffrey Muir, Dave Murdie, Emma Nordstrum, Piotr Orczewski, Ruth Panes, Lucy Parker, Jonathon Pettitt, Derek Pitman, Hugo Pinto, Nick Plunkett, Dalia Pokutta, Richard Potter, Antonio Ramon, Steven Rawling, Simon Reames, Phil Roberts, Renate Rosa, Rob Scott, Elaine Simpson, Andy Sole, Oliver Spiers, Kirsty Squires, Mark Stewart, Ida Szatkowska, Kimberley Teale, Anne Thom, Gareth Thomas, Jessica Tibber, Jonathon Watts, Tom Wells, Alan Whitaker, Sam Whitehead, Kayleigh Whiting, Gary Wickenden, Rebecca Wills, Tristan Wood-Davies and Dane Wright.

The Neolithic houses were principally excavated by Mark Bagwell, Elina Brook, John Powell, Peter James, Tom Wells and Andy Sole. Rob Scott excavated the Beaker burial.

Specialists and Post-Excavation team

Phil Andrews, Catherine Barnett, Philippa Bradley, Ellie Brook, Nigel Cameron, Nicholas Cooke, Paul Cripps, John Crowther Niall Donald, Michael Grant, Jessica Grimm, Kevin Haywood, Lorrain Higbee, David Holman, Elizabeth James, Grace Jones, Laura Joyner, Stephanie Knight, Richard Macphail, Lorraine Mepham, Jacqueline I. McKinley, J.M. Mills, Quita Mould, Nicki Mulhall, Jens Neuberger, David Norcott, Peter Northover, Ben Roberts, Fiona Roe, John Russell, Jörn Schuster, Simon Skitterell, David Smith, Rosie Smith, Emma Traherne, Lynn Wootten and Sarah Wyles.

Wessex Archaeology are extremely grateful to CEMEX UK, and their consultant Adrian Havercroft (The Guildhouse Consultancy), for commissioning and funding the archaeological excavations at Kingsmead Quarry, Horton.

Windsor museum exhibition

We are delighted to announce that finds from the excavations at Kingsmead Quarry, Horton, have been placed on semi-permanent display at Windsor Museum.

The display focus' on the discovery of a rare Beaker burial. The woman of importance, or ‘queen’ was found with gold and amber grave goods, as well as a Beaker pottery vessel. All will be on display at the museum for at least 1 year.

The exhibit also includes finds which explore the secrets of the site as we present the hidden past beneath Horton’s ancient landscape and uncover the imprints left by farming, community and ritual activity.

A travelling exhibitions was also produced, which can be seen below.

To view the flickr gallery for this site follow this link