Our journey through the archives at Wessex Archaeology in Salisbury moves to the North East corner of the medieval city. This area, which occupied the land between Castle Street and Endless Street, has undergone considerable changes since 1987 when the first phase of work was undertaken. Demolition of Anna Valley Motors workshops and filling station, which faced onto Castle Street, preceded construction of office accommodation for Friends Provident insurance and restricted the area that was available for excavation. Despite this inconvenience, it was possible to investigate the projected line of the city defences to examine their presence, completeness and appearance. Documentary evidence shows that permission was granted to enclose the city in 1227 although the city authorities apparently demonstrated very little enthusiasm to complete the work and, as last week’s entry suggested, the circuit may never have been completed.

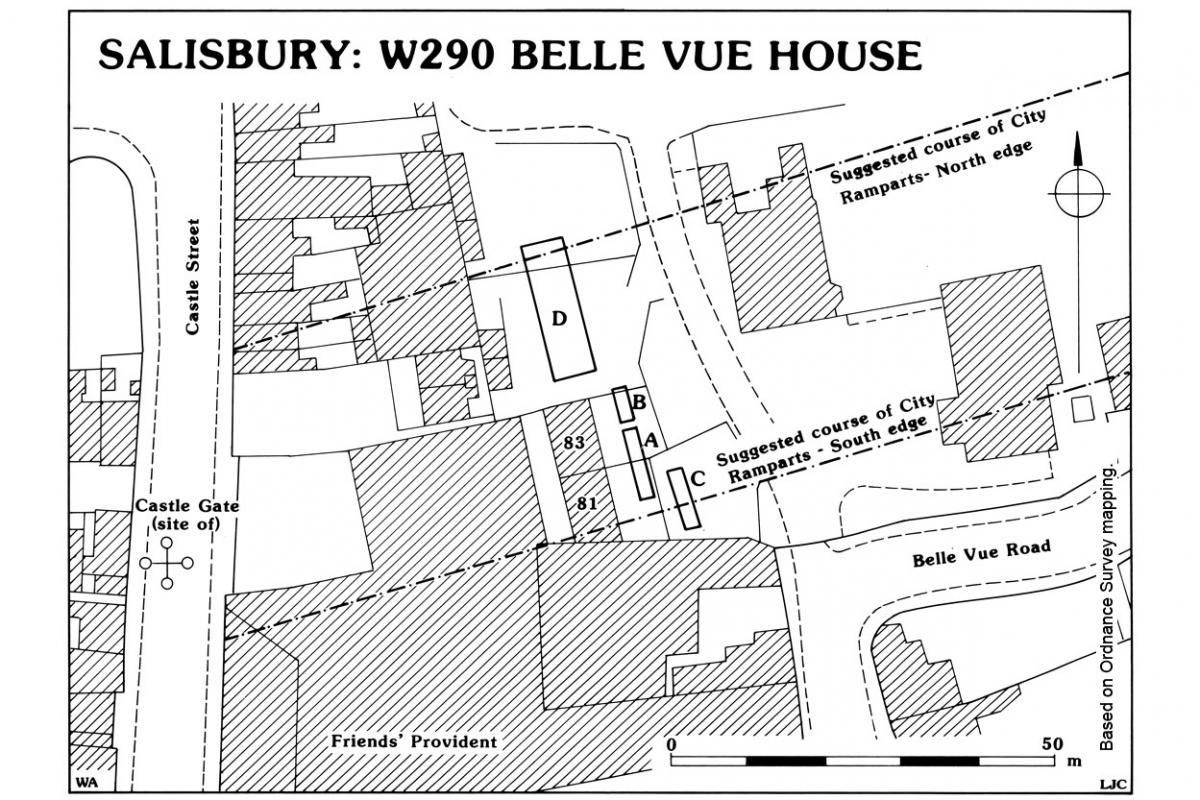

The first investigations were undertaken by the Trust for Wessex Archaeology, now Wessex Archaeology, who dug four trenches to locate the ramparts at Belle Vue House. As at Bourne Hill no traces were found of the bank or the outer ditch, however, excavation in the fourth trench revealed a large cluster of pits, with pottery dating between 1250 and 1350. This was a significant discovery at the time; very few rubbish pits had been found in Salisbury. Archaeologists had speculated that this may have been due to the high water table and suggested that alternative forms of rubbish disposal may have operated in the city. Pits have now been found elsewhere in the city, as will become apparent in future weeks, although this cluster at Belle Vue House still forms an important group and is frequently included in discussions about rubbish clearance in medieval Salisbury.

The report also noted the presence of a ditch which may have been part of Hussy’s Ditch, a watercourse which fed the medieval system of water courses that ran through Salisbury. This network of water channels was a distinctive feature of the street planning of medieval Salisbury and was designed both to provide fresh water but also to function as a drain, a combination that was distinctly impractical and insanitary.

This phase of activity was succeeded by a series of post holes and slots which related to later medieval and early post medieval structures, suggesting that some form of settlement may have encroached beyond the original boundaries of the city. The entire sequence was sealed by a deep deposition of ‘black earth’ which contained only post medieval pottery and a capping of modern topsoil.

Archaeologists returned to the site in 2017 when the Friends Provident building was demolished to make way for further redevelopment. Six trenches were dug close to the earlier trenches and similarly produced no evidence of the city ramparts. The trenches revealed a small number of features dating from the early medieval to the 19th century. These results included an east-west aligned ditch which was also considered to be a candidate for Hussy’s Ditch, although, intriguingly, it did not align with that plotted by the 1987 excavation.

Section through the possible candidate for Hussy’s Ditch, the excavated section of a small pit, and a structure visible in the section of Trench 2

Medieval features were represented by a possible drainage gully and a pit, but no other medieval pits were revealed in contrast with the earlier excavations.

The report confirmed the thickness of ‘black earth’ and concluded that this material had been dumped to make up the ground where the natural silty-clay ‘brickearth’ may have been extracted. This material was used extensively in Salisbury as daub in house construction, although no quarry pits were defined. Similar soil accumulations will be encountered in future entries from within Salisbury.